News

How hospitals got richer off Obamacare

After fending off challenges to their tax-exempt status, the biggest hospitals boosted revenue while cutting charity care.

A decade after the nation’s top hospitals used all their advertising and lobbying clout to keep their tax-exempt status, pointing to their vast givebacks to their communities, they have seen their revenue soar while cutting back on the very givebacks they were touting, according to a POLITICO analysis.

Hospitals’ behavior in the years since the Affordable Care Act provided them with more than 20 million more paying customers offers a window into the debate over winners and losers surrounding this year’s efforts to replace the ACA. It also puts a sharper focus on the role played by the nation’s teaching hospitals – storied international institutions that have grown and flowered under the ACA, while sometimes neglecting the needy neighborhoods that surround them.

And it reveals, for the first time, the extent of the hospitals’ behind-the-scenes efforts to maintain tax breaks that provide them with billions of dollars in extra income, while costing their communities hundreds of millions of dollars in local taxes.

One example of the hospitals’ efforts to remain tax-free: the soaring, minutelong TV commercial that popped up on stations across Western Pennsylvania in 2009 by the University of Pittsburgh Medical Center, the area’s flagship hospital and one of the largest teaching hospitals in the country.

“UPMC is proud to be part of our city’s past, present and, more importantly, its future,” the narrator enthuses, as the camera pans around Pittsburgh scenes of priests, grocery-store workers, even a ballet dancer before coming to rest on the sprawling medical campus — one of the five largest in the world.

At the time, Congress was considering not only whether to remove tax-exempt status for teaching hospitals, a cause of Sen. Chuck Grassley (R-Iowa), but also whether to add requirements forcing hospitals to do more for the low-income, urban communities in which so many of the top hospitals are located. And local leaders in many states were attempting to claw back billions of dollars in forgone tax revenue — a battle that would soon break out between UPMC and the mayor of Pittsburgh, too.

But the hospitals, aided by their good-neighbor initiative, prevailed. The ACA did nothing more to force the hospitals to share their revenue with their neighbors or taxpayers generally.

The result, POLITICO’s investigation shows, is that the nation’s top seven hospitals as ranked by U.S. News & World Report collected more than $33.9 billion in total operating revenue in 2015, the last year for which data was available, up from $29.4 billion in 2013, before the ACA took full effect, according to their own financial statements and state reports. But their spending on direct charity care — the free treatment for low-income patients — dwindled from $414 million in 2013 to $272 million in 2015.

To put that another way: The top seven hospitals’ combined revenue went up by $4.5 billion per year after the ACA’s coverage expansions kicked in, a 15 percent jump in two years. Meanwhile, their charity care — already less than 2 percent of revenue — fell by almost $150 million per year, a 35 percent plunge over the same period.

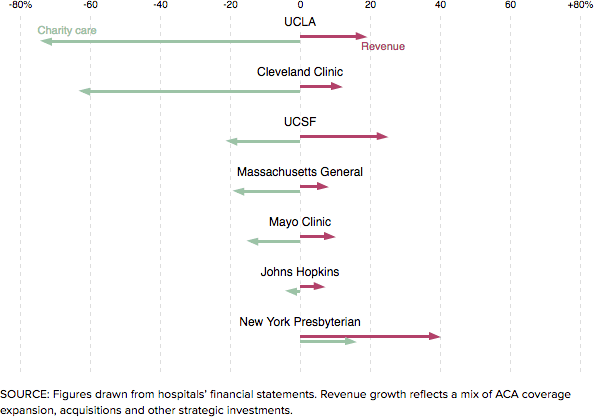

Revenue up, charity care down

While operating revenue increased under Obamacare for not-for-profit hospitals like the Cleveland Clinic and UCLA Medical Center, the amount of charity health care they provided fell. For example, while UCLA saw operating revenue grow by more than $300 million between 2013 and 2015, charity care fell from almost $20 million to about $5 million.

Hospitals justify the billions of dollars they receive in federal and state tax breaks through a nearly 50-year-old federal regulation that simply asks them to prove they’re serving the community. (Some states have taken a stricter approach for their tax breaks.) And while hospitals acknowledge that their charity care spending has fallen — pointing to the fact that a record number of Americans are now insured under the ACA — some leaders say the trend could reverse itself if the ACA is repealed.

Hospitals also defend their tax-exempt status by pointing to their total community benefit spending, a roll-up number that can include free screenings and local investments but also less direct contributions, like staff education or hospitals’ internal metrics for when they say there is a gap between what they charge for services and what Medicare or Medicaid pays them.

But in many cases, top hospitals’ community benefit spending has remained flat or declined since the ACA took effect, too. For example, Massachusetts General Hospital in Boston, which has been ranked as the best hospital in the world, spent $53.8 million on community benefits in 2015, down from $62.1 million in 2013, even as its total annual revenue went up by more than $200 million.

Advocates say that not-for-profit hospitals are failing in their responsibilities to their communities, which are beset by rising rates of opioid addiction, diabetes, asthma and other serious but treatable conditions.

“Are they doing enough? I can give you a one-word answer: No,” said Charles Idelson of National Nurses United, a labor union that’s fought with hospitals over their community contributions. “So many of these hospital chains, their clear priority is their budgetary goals or their profit margin.”

A record profit margin

Obamacare may have been a mixed blessing for those seeking coverage through the state exchanges, some of which have seen double-digit annual premium hikes, but it’s been a clear boon for the nation’s hospitals.

Multiple studies have linked the ACA’s coverage expansion to improved financial performance, with one analysis finding that hospitals’ profit margins went up by 25 percent in states that expanded Medicaid in 2014. Overall, the industry boasted an 8.3 percent profit margin that year, according to the most recent figures published by the American Hospital Association. That’s the highest performance on record — more than triple the industry’s 2.6 percent profit margin in 2008, amid the recession and before the Obama administration began pushing its health care reforms — and it’s only invited scrutiny from advocates and researchers who say that it’s a sign the system is broken.

Gerard Anderson, a health care economist at Johns Hopkins University, co-authored a study in 2016 that found 7 of the 10 most profitable hospitals in the United States are technically not-for-profit hospitals. “The taxing system may not be working properly if nonprofit hospitals are making a lot of profit and not necessarily putting it back into the community,” Anderson said at the time.

Hospitals dispute that Obamacare has been the engine of their recent success. “We would not attribute our solid financial performance to ACA,” said a spokesperson for the Mayo Clinic — the top-ranked hospital in the US News rankings, which cleared $1 billion in combined operating income in 2015 and 2016. “It’s a result of a fiscal discipline, focus on creating efficiencies, generous philanthropic donations, as well as research funding from NIH and revenue created through our commercialization efforts.”

And they add that looking at profits doesn’t tell the full story, especially because they’re funneling those dollars back in the form of jobs and other civic benefits. For instance, hospitals are the largest employer in many major cities and most congressional districts.

Johns Hopkins Health System, for instance, said it was responsible for more than 22,000 jobs in Baltimore City — and nearly $1.8 billion in total economic impact.

Johns Hopkins Hospital in downtown Baltimore. (Getty Images)

But the job gains don’t necessarily help their close neighbors – or improve their health. Anderson, for one, was skeptical that big hospital revenues translate to community improvements. Instead, they often lead to multimillion dollar renovations, more executive compensation and other big-ticket spending items that don’t actually benefit nearby residents.

“A lot of the communities where these hospitals are located are having financial difficulties,” he said. “The hospitals, which are making money, aren’t contributing to the financial reserves of that community. They are obviously employing people, but they are earning substantial profits and not paying any of those profits to the communities.”

Community benefits

Hospitals are required to provide community benefits in order to keep tax exemptions that, collectively, are worth billions of dollars. But the benefits they cite combine a range of services that don’t always directly benefit their communities, and free care tends to be a small and dwindling percentage.

For example, in 2013, the majority of the Cleveland Clinic's community benefit was made up of the hospital's Medicaid shortfall – the gap between Medicaid payments and the Clinic’s self-determined costs for those procedures – and education costs mostly associated with training residents, fellows and other clinical staff.

Other categories, like financial assistance and outreach programs, have a more direct impact on the local community but made up a minority of the Cleveland Clinic's community benefit.

In 2015, as Obamacare’s coverage expansion took full effect, these more locally beneficial categories shrunk further as the hospital wrote off additional Medicaid-related costs and spent more on educating their own staff.

Financial assistance dropped more than any other category, falling from $169 million to $69 million, as the uninsured rate plunged.

A bizarre contrast

It’s set up a bizarre contrast. Many U.S. cities boast hospitals that are among the best in the world, but the communities around those hospitals might as well be the Third World.

Walk five minutes off the Hopkins campus in downtown Baltimore and you’ll arrive at the city’s Madison-East End neighborhood, where the poverty is both visible — cracked sidewalks, empty storefronts and more than three times as many vacant lots per house than in the rest of the city — but also silently killing residents. The death rate in the neighborhood is 30 percent greater than the rest of the city and mortality from cancer, stroke and heart disease is more than twice as high.

One striking figure: The life expectancy rate in Madison-East End is less than 69 years. That’s lower than the life expectancy in impoverished countries like Bangladesh, Turkmenistan and North Korea. It’s also subtly at odds with the message Hopkins sells to the rich patients it courts from around the world, encouraging them to come to a hospital that’s akin to a health mecca, even if it’s actually located in a rundown area.

“Poor communities around hospitals tend to lack simple conveniences, like grocery stores stocked with healthy, inexpensive food or even places to play or exercise outside safely,” says Elizabeth Bradley, president of Vassar College and co-author of “The American Health Care Paradox,” which offers reams of research on how living in such neighborhoods leads to worse health and social instability. “The paradox is that we focus on and invest in areas like hospital care when social determinants matter so much more,” she says.

And for many residents, a vicious cycle begins when they’re young, as Bradley and others have chronicled; many of these neighborhoods have high crime rates, and exposure to violence increases violent behavior among children. It’s also hard for them to escape their circumstances: One 23-year-long study of Baltimore schoolchildren found that, as they grew up, the children born into low-income families generally stayed in the same socioeconomic bracket as their parents.

The nation’s top hospitals do invest in these communities; Hopkins, for example, offers intern training programs and free health education among its community investments. Not-for-profit hospitals are encouraged to publicize these initiatives, so their tax exemptions are not lost.

“It is essential that hospitals voluntarily, publicly and proactively report to their communities on the full value of benefits they provide,” the American Hospital Association instructed its members in 2006, after a series of regulators and Congress began reviewing hospitals’ tax-exempt status. The ACA further codified requirements that tax-exempt hospitals must report on their community benefit activities.

But based on their own self-reports, these hospitals clearly could be doing more. A POLITICO review of community benefit activities reported by these top hospitals found that the organizations counted activities like sponsoring races and hosting lectures toward their community benefit spending. Many of the dollars that hospitals report as “community benefit” are more accurately an accounting trick — the shortfall that hospitals incur when Medicare or Medicaid reimburses the hospital at less than the organization’s price.

Idelson of National Nurses United says this squares with his own organization’s reviews, which illustrate that hospitals approach these investments as “big businesses,” and community benefit programs are too often “their marketing schemes.”

“Hospital staff are going to a marathon and handing out water bottles, and the hospital is calling it a community benefit,” he added. “To us, a community benefit is something that actually improves the health of a community.”

That’s one reason why civic leaders in Baltimore and beyond say they want to see hospitals spend even more on what’s increasingly known as “population health,” or addressing the social needs of residents so they don’t need to visit the hospital in the first place. But there’s no formal requirement to do so. And because hospitals are such deep-pocketed, long-lasting institutions, they can wait out many would-be reformers.

“How do you [convince] an organization that’s existed for decades when you’re only there for a few years? It’s a challenge,” said Abdul El-Sayed, who served as Detroit’s health director from 2015 to 2017. He’s now running for Michigan governor. El-Sayed worked with hospitals to secure public investments like lead screening — a top-of-mind issue for residents in a city just miles away from Flint — but said he had problems winning further compromises.

Hospitals at war

The struggles of El-Sayed and other state and local leaders illustrate what most reformers already know: The best way to pressure hospitals to do more for their communities is at the federal level.

And the best opportunity came in 2009, while Congress was gearing up for what would become the Affordable Care Act. Already reeling from the recession, not-for-profit hospitals were loath to pay an additional $13 billion in taxes if their status changed.

But there were some strong arguments in favor of it, at least politically. Major teaching hospitals kept getting caught chasing dollars from patients who were too poor to pay, such as when The Wall Street Journal detailed how the prestigious Yale-New Haven Hospital was putting massive liens on poor patients and their families — including a 77-year-old dry cleaner slowly paying off the thousands of dollars in interest from his wife’s cancer treatment. She had died 20 years earlier.

Lawmakers led by Grassley, the powerful Iowa Republican, felt the best response would be for the federal government to tighten the loophole that let those high-profile hospitals — and nearly 3,000 others — essentially self-define whether they deserved to be tax-exempt.

So hospitals went to war.

The inside story of how hospital tax exemptions factored into the ACA negotiations was widely overlooked at the time and, until now, mostly untold.

But it begins with the 83-year-old Grassley, the senator who remains Congress’ most reliable investigator of charities and their uncharitable behaviors, more than a dozen current and former Senate staffers told POLITICO. And he might never have gotten involved if not for the American Red Cross — and the Sept. 11, 2001, terror attacks.

As The New York Times and others reported in 2002, the Red Cross received nearly a billion dollars in donations in the seven months after the attacks. But Red Cross executives decided against offering those contributions entirely as relief, electing to bank almost $400 million rather than spend it right away. That didn’t sit well with Grassley, then the ranking member of the Senate Finance Committee, who led an investigation into the group’s operations, accused its chief of trying to mislead Congress and ultimately pushed to restructure the Red Cross board through legislation.

(To this day, Grassley is still skeptical of the Red Cross. In June 2016, he released a 309-page report concluding that the Red Cross mismanaged its Haiti relief effort, and in March he reintroduced legislation to increase transparency of the organization.)

The battle with the Red Cross began a years-long pattern. A well-regarded nonprofit would get attention for mishandling its funds. A newspaper would write it up. And Grassley would spring into action with detailed requests and subpoenas, ultimately taking him into conflict with Christian ministries, nature conservatories and even the United Way.

He’s a “good government guy,” said former Sen. Max Baucus (D-Mont.), who alternated with Grassley as the Finance Committee chairman or ranking member for years and teamed up on investigations into charitable organizations. Their partnership was intended to transcend partisanship, both men say. (“If Chuck asks you something, it’s like I asked you for it,” then-chairman Baucus once told officials who were dragging their heels on responding to a Grassley request.)

“We didn’t have a subcommittee on nonprofits, but if we did, Grassley would have been the chair,” said Russ Sullivan, who served as Baucus’ top aide.

By 2005, Grassley was chairman of the Finance Committee himself and had found a major target for his investigations: The nation’s 3,000 or so not-for-profit hospitals, which had spent decades inching away from their original charitable missions and increasingly acting like big businesses.

“Hospitals were suing patients who couldn’t pay,” said Theresa Pattara, who was an IRS staffer assigned to the Finance Committee at the time. “It was like trying to get blood from a stone.”

The IRS had once required that tax-exempt hospitals provide free or heavily discounted care to poor patients. But after the creation of Medicare and Medicaid, which dramatically reduced the number of indigent patients, hospitals in 1969 got the agency to relax its rules and allow them to keep their valuable tax exemptions if they provided “community benefit,” a more expansive definition that included charity care but also other activities that advanced patients’ health. Many hospitals included new construction, capital expenditures, even executive perks as community benefits.

It was a nebulous standard that galled Grassley, who led a multiyear investigation into the behavior of 10 hospitals and health systems, including the Cleveland Clinic and New York-Presbyterian Hospital, and convened a series of embarrassing hearings for the health care industry. At one September 2006 hearing, he hinted that core practices — from executive compensation to board structure — needed to be overhauled.

“Some nonprofit hospital executives enjoy the best hotels and great meals, all subsidized by the taxpayer,” Grassley said, as health care leaders nervously looked on. “I find it especially troubling that executive after executive is having country club dues paid for by nonprofit hospitals.”

The hospital industry fought back. Major systems took out ad campaigns touting their charitable work. Hospitals quickly moved to voluntarily disclose their community benefit spending and began issuing new annual reports. The powerful American Hospital Association mobilized its lobbyists to try and win over congressmen. But Grassley kept up the pressure.

“Grassley would have senators coming up and saying, ‘why are you bothering the only hospital in my district?’” Pattara recalled. But the Iowa senator wouldn’t back down, having memorized reams of statistics — like executives’ million-dollar salaries — as a counterargument. “Grassley would say, ‘do you know what they’re paying their CEO?’ and the congressmen would be taken aback,” Pattara added. “I loved Grassley for that.”

Grassley’s inquiries and mounting public scrutiny invited more investigations. A Joint Committee on Taxation report, requested by then-House Ways and Means Committee Chairman Bill Thomas, concluded that the hospital industry in 2002 got $12.6 billion in tax savings, as it not only escaped income, sales, and property taxes but also used tax-exempt debt to finance major projects. The financial benefits for those hospitals were actually even larger; for instance, the figure didn’t include the billions of dollars in tax-free donations that hospitals also received every year.

By 2007, Grassley was openly floating the idea that hospitals must provide at least 5 percent of their revenue in exchange for tax exemption. But aides say this was mostly a negotiating ploy to scare the industry rather than fight for explicit requirements on hospitals to provide charity care or be taxed.

Grassley pushed for reporting requirements instead. The IRS ended up redrawing its Form 990, the document that charitable organizations must submit annually, and adding a new section — Schedule H — that specifically required hospitals to detail their community benefit activities.

Grassley had a few reasons for avoiding more punitive measures on hospitals. One was that he didn’t want to be a Republican who was linked to imposing new taxes, aides say, but rather viewed as a legislator who shined a light on dark sectors. Another was that the committee was mostly relying on anecdotes and its own limited investigation into the $1 trillion industry.

“Ideally, you legislate from facts and data,” says Pattara, who returned to the IRS to work on the new Schedule H addition. “And there wasn’t enough data yet” to call for new legislation to reshape the hospital industry.

Digging in for a battle

Hospitals had escaped the biggest threat: New federal regulations. But they were still worried about a series of local challenges, pushed by state attorney generals after regulators in Illinois in 2003 stripped a pair of hospitals of their property-tax exemptions.

The Cleveland Clinic got caught up in one of those fights after it tried to get exemptions for a pair of satellite offices and local regulators said the buildings weren’t providing necessary charity care. The battle dragged on for more than a decade before Ohio’s Republican tax chief in 2012 reversed the previous Democratic administration’s denial of the property-tax breaks.

For opportunistic state leaders, not-for-profit hospitals represented a chance to make a major statement — and recoup some tax dollars as state revenue was declining. Illinois Attorney General Lisa Madigan pushed a bill in 2006 that would have required hospitals to spend 8 percent of their operating budget on charity care. Attorneys general in Kansas, Minnesota, Ohio and other states also began probing hospitals’ spending and pushing for tougher definitions of community benefit standards.

Hospitals dug in, with the American Hospital Association providing air cover and refining the industry’s messaging. Ads began blanketing state capitols, singing the praises of local teaching hospitals. Health care leaders started to aggressively release reports, touting their spending on community benefits. National organizations emerged to offer crisis communications on how not-for-profits could preserve their status.

In Illinois, the Madigan bill was defeated, as hospitals repeatedly steered lawmakers away from imposing new legislative requirements on their charity care; instead, the state ended up simply convening commissions and offering recommendations. It was a case study in how to derail legislation. The industry “has tremendous clout in [state capital] Springfield and has been able to water down any charity care proposals as to make them meaningless,” James Unland, a hospital consultant, said at the time. A subsequent 2012 law that exempted Illinois hospitals from property taxes if they met certain charitable standards has been tied up in litigation for years.

The regional battles also put not-for-profit hospitals on high alert: If they weren’t careful and proactive, their decades-old property tax breaks could disappear if a local board or school district decided to move against them.

Reason to be confident

Back in Washington in late 2008, Democrats had claimed control of Congress and were readying their health care bill. They were also eyeing how best to negotiate with the health care industry, which had fiercely resisted the Clinton-era health reforms and ultimately helped kill them. This time, Baucus’ team reasoned, they needed to get all the major trade groups to the table — and keep them there.

“We had done this whole analysis of every single sector going into ACA,” said a former Senate aide who helped craft the bill. “What do they have to win? What do they have to lose? What are they most afraid of?”

For hospitals, losing tax-exempt status was on their list of potential pain points, and that gave Democrats a bargaining chip with the influential industry. “As long as they were winning on parts, you could press on the losses,” the aide said.

It also gave Democrats a carrot to try and win over Grassley, as Baucus sought Republican votes in hopes of making his committee’s health care legislation into a bipartisan bill.

Baucus had reason to be confident that his longtime collaborator would support a major health care push. In a plan that hasn’t previously been reported, the two men came close to going to the McCain and Obama campaigns in late 2008 in an attempt to secure a commitment — from whoever was president — to work on health reform in 2009. The idea harkened back to 2001, when Baucus crossed the aisle to work on tax reform with Grassley after the previous year’s controversial presidential election.

Sens. Max Baucus (D-Mont.) and Chuck Grassley (R-Iowa) preside over a 2009 Senate Finance Committee hearing. The committee passed health care legislation that was considered the most moderate of five health care bills before Congress. (Getty Images)

The two senators ultimately didn’t make their joint pitch to the McCain and Obama camps. “We just couldn’t pull the trigger,” said Sullivan, Baucus’ key aide. But it laid the groundwork for the negotiations to come. “Baucus was convinced that Grassley would be willing to join him on health care legislation,” Sullivan added.

Before the ACA, “we weren’t even contemplating enacting anything around tax-exempt hospitals,” said Pattara, who had rejoined the Finance Committee as Republicans’ tax counsel in 2008.

In early 2009, Democrats’ tactics seemed to be working, as hospitals engaged in negotiations and Grassley expressed support for a health reform compromise. A May 2009 policy paper on proposals to fund the expansion of health coverage — co-authored by Baucus and Grassley — floated a requirement that hospitals “provide a minimum annual level of charitable patient care.”

Early drafts of the ACA legislation specifically included new restrictions on whether hospitals could qualify as tax exempt, as a give to Grassley. But it wasn’t a high priority for Baucus and other Democrats.

“The things that the Democrats were focused on were mostly about [insurance] coverage and subsidies,” a former aide said. “Everybody had a pet project in there — and they paid attention to their pet project.”

On the other side of the table, there was a schism between the hospital lobbyists. The Catholic Health Association, which was working with the Obama administration on the reform bill, explicitly defined community benefit as services rendered. But the American Hospital Association, which was more combative in its negotiations around the bill, took a harder stance on tax exemptions: It wanted a more expansive definition of community benefit that included patients’ bad debt and even Medicare- and Medicaid-related underpayments.

Meanwhile, the Federation of American Hospitals — the for-profit lobbying group — had produced evidence that its members, which paid taxes, provided just as much charity care as their not-for-profit peers.

The industry’s inability to align its message hampered its own negotiating position. But lobbyists for the Catholic Health Association and the American Hospital Association agreed: They couldn’t sign off on any measure that revoked the exemption. It was too valuable. Large health systems were getting tens of millions of dollars in annual benefits from their tax exemptions.

So they hammered out a compromise: Hospitals would need to conduct a community health needs assessment every three years and report their findings to the IRS. The findings would need to incorporate broad feedback from the hospitals’ constituents, be publicized “widely” and lead to changes as necessary. The assessments would help the IRS determine whether tax exemptions were warranted — and if hospitals didn’t comply, they’d have to pay a $50,000 excise tax. The bill also formalized a series of changes to hospital policies, like requiring them to publicize their financial assistance rules.

All things considered, the proposal had relatively little bite, and the rest of the inducements offered by negotiators — like the health law’s planned coverage expansion — were quite generous to the industry. The hospitals publicly threw their support behind the ACA in July 2009.

“Their best play [was] watering it down as much as possible and kicking it to Treasury to make it difficult to implement,” a former aide said, referencing the new community-needs reviews.

Hospital lobbyists agree: Their strategy was delaying and focusing on bigger-ticket items, like near-term changes to Medicare payments. “We knew we couldn’t fight the idea of more transparency,” said one lobbyist who’s still employed by the industry. “We picked our battles and hoped Grassley wouldn’t make too much noise.”

But Grassley had his own troubles. Besieged by protesters at town halls and attacked by tea party activists in August, the Iowa senator ultimately signaled he couldn’t support the ACA legislation. The hospital industry stayed mum as Grassley dropped out.

“Once Grassley was not part of it, they didn’t come back to us and say, OK, now that he’s not on board, we want to take this out,” a former Democratic aide said.

Hospital lobbyists say that was a deliberate decision. “The previous years had made clear, this was a losing issue for us,” said a lobbyist. “The less we talked about tax exemptions, the better.”

Sullivan, Baucus’ key aide, helped track the provision and made sure it remained in the final bill.

Once again, the hospital industry had dodged a major challenge to its tax exemptions — perhaps the most significant in 40 years.

Who should be a nonprofit?

Rolling out the new charity assessments and vetting hospitals fell to the IRS, which spent several years working on the new 501(r) tax section and the ACA’s other tax provisions — the most significant changes to the tax code since Congress’ 1986 tax reform bill.

But the charity reviews forced the IRS into an unusual position, former staffers who worked on implementing the ACA told POLITICO: The agency didn’t really have the experience or expertise to determine whether hospitals should be not-for-profit.

“Using the IRS as an instrument to achieve these important goals … was not the best fit,” said Jason Levitis, who led the Treasury Department’s implementation of the Obamacare regulations. “Why is the IRS the one we want to be [investigating] hospitals’ business about how they’re serving poor people?”

The IRS has largely shied away from battles over revoking tax-exempt status, whether for hospitals or any other organizations. The agency’s most high-profile fight was a two-decade battle over the tax-exempt status of the Scientology organization — which ended after the IRS was overwhelmed with lawsuits and ultimately granted Scientology’s request to be considered as a church.

“It’s not a fight that the IRS wants to have,” said one current staffer, referring to the often politically charged process of removing a group’s tax-exempt status.

Instead, Levitis and others suggest that the administration’s health care agencies should have played a central role in determining if hospitals should be tax exempt. “Think about institutional competence,” Levitis said. “If you were going to choose a government entity … to be policing tax-exempt status, is the IRS [really] the agency with institutional competence — or is there a better option?”

Meanwhile, ACA standards aren’t specific enough to give any agency clear guidance on when to remove tax-exempt status, critics complain.

Community-health-needs assessments are easy to game, experts familiar with the reviews told POLITICO. One consultant told POLITICO about getting a call from executives who were desperate and needed help before submitting their hospital’s assessment; the consultant ended up dictating stock language over the phone, having never even visited the hospital or its community. “They’re a joke,” the consultant said of the ACA standards, arguing that the reviews are mostly a public-relations exercise.

Not a single hospital has lost its tax-exemption because of the new measures in the ACA.

Nonetheless, hospitals have had difficulty complying even with the law’s relatively light requirements. As of an IRS review last year, one-third of surveyed hospitals had been referred for further compliance checks.

The IRS has had its own problems, failing to promptly file required annual reports to Congress about what it’s learned about hospitals’ compliance. That’s been a source of frustration to Grassley, who despite not voting for the ACA, has pestered the agency to fulfill its responsibilities under the law.

It’s also vexed Democrats. “The problem is that the executive branch, first under President Obama and now under President Trump, has not followed through and done its job under the law,” Sullivan said.

A forgotten fight

It’s not clear who, if anyone, will carry the torch for new regulations or even prod the IRS to put more teeth into its oversight. Grassley has moved on to chair the Senate Judiciary Committee, where his jurisdiction is less focused on hospital issues than it was when he led the Finance Committee. Several of his former staffers now work either directly for hospitals or on behalf of them.

One former Grassley aide points out that since the Trump White House is pushing the idea of major tax reforms, there’s an opportunity to review how hospitals’ tax exemptions are treated. But the Republican Party historically has been hesitant to move against hospitals, and the issue of hospitals’ tax-exempt status isn’t on the table in the negotiations to repeal and replace Obamacare.

Meanwhile, many struggling communities are facing a difficult dilemma: If they pressure hospitals to do more for the families and children who live near them, they risk alienating the one local business that’s growing.

For many poorer cities, hospitals have emerged as anchor institutions while sectors like manufacturing die off. The seven top hospitals reviewed by POLITICO employ about 150,000 people on their main campuses. About 35,000 people work for the Mayo Clinic in Rochester, Minnesota, alone — equivalent to about 30 percent of the city’s entire population.

Pressured by city officials, some tax-exempt hospitals have hammered out voluntary contributions, known as payments-in-lieu-of-taxes, or PILOTs, to help offset the cost of city services like police and fire protection. But those payments are usually a small fraction of the actual cost of those services, while the value of hospitals’ tax exemptions continues to rise.

Boston’s Massachusetts General Hospital would have owed more than $55 million last year if it was taxable. Instead, the city requested that the hospital pay less than $7 million through its PILOT program.

National Nurses United has repeatedly pushed legislation that would require hospitals to spend a percentage of their revenue on charity care — a proposal that hospital executives have fought. The bill was closest to breaking through in California, although it’s been met again and again by aggressive lobbying. The legislation “imposes vague and unrealistic standards on nonprofit hospitals,” Martin Gallegos of the California Hospital Association — and a former California assemblyman — warned his former colleagues in the Legislature in 2013.

Top hospitals hope to gain political advantage by strategically maintaining ties with prestigious civic leaders. Hopkins’ board is packed with influential and well-known sons and daughters of Baltimore. The vice chairman was a top CIA official and the CEO of Baltimore-based Alex. Brown & Sons, the nation’s oldest investment banking firm.

Of course, it’s not popular to take on hospitals, which have reputations as lifesavers, and lawmakers haven’t shown interest in a sustained political fight. Luke Ravenstahl, then-mayor of Pittsburgh, launched a lawsuit against UPMC in 2013, seeking tens of millions of dollars that he said the city was losing in taxes. UPMC countersued, and Ravenstahl’s successor dropped the fight in 2014, saying that he wanted to negotiate PILOTs “in good faith” with UPMC and other not-for-profits. Three years later, those negotiations continue without a deal.

But to truly bend health care’s cost curve, policymakers need to get hospitals to do more for their needy neighbors while reining in runaway costs, said Anderson, the Johns Hopkins University economist. For all of the attention on the pharmaceutical sector’s bad actors and practices, just 10 percent of health care spending is on prescription drugs. Instead, more than 30 percent of health care spending goes toward hospitals — amounting to more than $1 trillion per year.

Taxes are one way of capturing those dollars and channeling them into necessary investments. And as long as the Affordable Care Act stays — and even if it goes away — tax-exempt hospitals have a duty to use all of the extra dollars to do more for their communities, advocates and analysts say.

“Tax-exempt hospitals could absolutely be doing more, given what they’re saving,” said Lauren Taylor, a co-author of “The American Health Care Paradox.” “I see a real opportunity for forward-thinking hospitals to make investments in local communities that do two things at once. Smartly invested dollars could both [protect] tax exemptions — and reduce financial risk by improving the community’s health.”

Reporting for this story was supported by a grant from the Commonwealth Fund through the Association of Health Care Journalists.

Original Post: http://www.politico.com/interactives/2017/obamacare-non-profit-hospital-taxes/