Labor Pains

Hospitals focusing on maximizing profits are cutting labor and delivery units, endangering pregnant patients and entire communities

By Rachel Berger

National Nurse Magazine - April | May | June 2022 Issue

Jennifer Hovie, RN, was absolutely stunned when she learned the birthing center she’d worked in for more than a decade would close.

“I read about it in the paper,” recalled Hovie. “It was just like a gut punch and then just honestly disbelief. It just seems like such a crazy thing to do.”

Hovie’s birthing center at Redwood Memorial Hospital was located in Humboldt County in Northern California, where 20 percent of the population lives in poverty and the infant mortality rate is nearly seven per thousand births, much higher than the state’s 4.6 rate.

The birthing center served a large area, with many patients driving 50 or more miles away to reach the facility. When the center closed, many patients were forced to travel an additional 20 to 30 miles to get obstetric care.

Local patients had the same concerns as Hovie. Kim Nichols, an EMT and paramedic in Humboldt County, was vehemently opposed to the closure, arguing the additional drive time is dangerous for families. She credits the birthing center’s expertise and location with getting her and her child safely through a very difficult birth.

“My last delivery was terrifying,” Nichols told a community paper in 2021. “My baby had a true overhand knot in the cord- if I had to wait any longer, that cord could have tightened – and my baby would have died.”

Nichols continued. “I could have easily become a statistic if I hadn’t had that quick access.”

Hovie worries about pregnant patients who need emergency services having to give birth or seek care in the emergency room at her hospital. “They do not have adequate training to deal with obstetrical emergencies because that’s not their focus,” and she said emergency departments lack fetal monitors. Many nurses don’t realize that labor and delivery RNs face a unique situation: They are actually caring for two patients, one of whom they can’t see.

The closure of Redwood Memorial’s birthing center and many other labor and delivery units around the country come as the United States is in the midst of what many call an urgent maternal and infant health crisis. We record the highest infant mortality rate compared with 10 other industrialized nations, with an average of more than 17 deaths per 100,000 births. And to add another dismal data point, the United States is the only industrialized nation where maternal mortality is rising. The statistics are even grimmer for women and people of color who give birth. Black people who give birth are at least three times more likely than whites to die as a result of pregnancy.

And now with the recent U.S. Supreme Court overturn of a constitutional right to an abortion, providers and experts fear that health outcomes will worsen even further for patients struggling with unwanted pregnancies.

As the population grows and needs for birthing facilities increase, hospital corporations are conversely shutting down labor and delivery units, neonatal intensive care units, or entire facilities in rural and lower-income urban neighborhoods. The reason? Nurses know these facilities are not profitable, or not profitable enough, for their corporate hospital chain owners.

Hospital ownership by national conglomerates and the closures of both entire hospitals and service lines are intrinsically linked. Over the last 25 years, the United States has seen a rapid increase in mergers and acquisitions in both for-profit and nonprofit health care systems. In 1994, just over a third of hospitals belonged to a system while the rest were independent. By 2018, more than two-thirds of hospitals belonged to larger systems.

Hospital corporations, not based in the communities in which they operate, have little vested interest in the well-being of local patients, instead focusing solely on profits and profit margins.

In the last two decades, rural counties, such as Humboldt, have been hit hard by the loss of hospitals and obstetric care units. More than 180 RURAL hospitals have closed since 2005. By 2014 more than half of all rural counties had no hospital that offered care for pregnant people even as 28 million women of reproductive age live in rural counties. More than three-quarters of rural counties in Florida, and more than two-thirds of rural counties in Nevada and South Dakota had no in-county hospital obstetric services at all.

California, where Redwood Memorial is located, recorded a net reduction of 14 labor and delivery units between 2010 and 2019, representing an 11 percent decline.

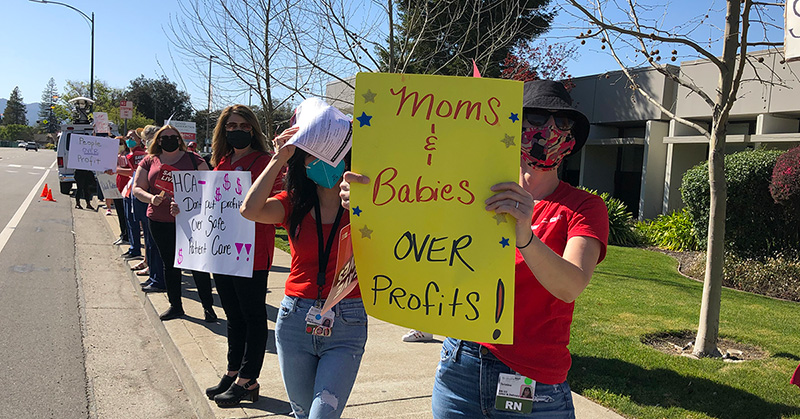

In April 2020, San Jose Regional Medical Center, which is owned by the country’s largest for-profit hospital chain HCA Healthcare and serves largely low-income patients in east San Jose, closed its labor and delivery ward despite nurses’ vocal and public protests.

Maureen Zeman began her 29-year tenure at the San Jose Regional Medical Center when it was owned by a non-profit hospital chain and said there have been profound and devastating changes at the hospital since HCA took over in 1996. When HCA announced they intended to close the obstetrics unit, Zeman was devastated.

“I was just angry and sad, just very, very sad. Sad for the patients, sad for the nurses that worked there. It was our heart and soul.”

“We did accept Medi-Cal for many, many, many years and then probably about eight years ago they got rid of their medical contract and our deliveries went from 300 to 30,” said Zeman. When the hospital stopped accepting Medi-Cal, the ob-gyn doctors left. Eventually the hospital began taking Medi-Cal again, but the damage was done. With the doctors gone, the patients didn’t return. “HCA is all about money. They wanted a service line that brought in a lot of money. They didn’t care about helping the community and doing what was best for the mothers that live near the hospital.”

The nurses fought back. They brought their pleas to the public and to local elected officials, but in the end, HCA refused to reconsider. HCA, the multi-billion dollar for-profit hospital system based more than 2,200 miles away in Tennessee, closed the unit.

Hovie said when the Redwood Memorial nurses joined community members to oppose their L&D closure, they felt like their voices were ignored by hospital management and by those making the decisions at the headquarters in Washington state. “We just felt there was no buy-in from anyone, and that the hospital had absolutely made up its mind.”

“You have too many people with perverse incentives making decisions,” said Monica McLemore, an associate professor in the nursing department at University of California, San Francisco. “If your only accountability is to your shareholders because you’re part of the national conglomerate of groups that own hospitals around the country that does not get the people we serve, the care that we need.”

Nurses at Regional and Redwood Memorial, owned by Providence, say another way their health systems justified closures was by orchestrating low birth rates. Besides doing things like no longer accepting Medi-Cal, the hospitals achieve this by failing to recruit, retain, and support family physicians or ob-gyn providers. Without providers to provide prenatal care and attend births at those hospitals, patients stop delivering their babies there. Then the hospital corporation cites those lower birth rates as rationale for the closures.

It’s not just California. Since 2010, Illinois has lost at least 16 labor and delivery units; 11 of those closures happened in neighborhoods with levels of child poverty far higher than the state average, including three where the percentage of children living in poverty was more than double the state average.

In 2018, the South Side neighborhood of Chicago, a community that is 93 percent Black, had six ob/gyn units. By the end of 2021, that number had dropped to just three. Among those shuttered, the labor and delivery unit at Jackson Park Hospital.

“I was heartbroken,” said Yulanda Clark, who worked in Jackson Park’s labor and delivery unit. “I thought it was really a loss to the community, the women, we serve. I really believe that we offered them high-quality care.”

Tresury Blake-Marlow gave birth to her daughter at the hospital and has received care there since she was a child.

“When I walk in the door, they know my name,” Blake-Marlow said at a town hall meeting in 2019. She noted how much she appreciated the all-Black female staff, “When I’m there I feel comfortable. It’s good to see people who look like you.”

Clark notes that because the nurses and doctors who worked in her labor and delivery unit were almost exclusively Black, they were culturally competent to care for their patients. “We understand them and are empathetic to them.” That trust, bond, and rapport -- which is always essential to nursing care -- is even more critical during an experience as intimate and vulnerable as childbirth.

Clark said while there had been mumblings of the unit closure for years, the nurses were surprised that it came just a few years after the hospital spent $4.6 million in state grants to renovate and expand the labor and delivery unit.

“Why would you invest so much in this state-of-the-art facility and not utilize it?” said Clark. As the nurses fought to keep the unit open, they found that the majority of households in the surrounding area didn’t know about the renovations. Clark questioned why the hospital spent millions in taxpayer money but then failed to inform the community, “It made no sense at all.”

“Some of them are absolutely struggling to find a ride into the hospital, finding gas money, and now we’ve put this greater burden on them. How do you decide: Do I pay my rent and feed the kids I already have or deal with something that I can’t see and I can’t touch and they’re telling me maybe it’s a problem, or maybe it’s not?”

Registered nurses, whose medical expertise and practice is grounded in a deep knowledge and understanding of their patients and community, are not just worried about birthing emergencies resulting from unit and hospital closures; they are afraid for their vulnerable Black, Brown, and low-income patients now facing new, routine challenges as ob/gyn services are cut and shuttered.

Hovie said many parents who don’t have easy access to transportation, or who are scraping by, will skip important prenatal care that many patients received at Redwood Memorial’s birthing center.

“Some of them are absolutely struggling to find a ride into the hospital, finding gas money, and now we’ve put this greater burden on them,” Hovie said, adding that some patients will now have to take a day off work to travel to get tests or care, where previously they could get to the birthing center and be seen within an hour or two. “How do you decide: Do I pay my rent and feed the kids I already have or deal with something that I can’t see and I can’t touch and they’re telling me maybe it’s a problem, or maybe it’s not?”

When Jackson Park announced its labor and delivery closure, doctors and nurses fought to keep the unit open, worrying about how the many patients who walked to the hospital or who used public transportation would be able to access services.

Zeman worried that when Regional closed, the hospital’s low-income and immigrant patients from East San Jose would not be able to get care anywhere else.

“We had a lot of patients that didn’t speak English, and a lot of them that didn’t have a significant other,” recalled Zeman. “They would come in with a mother or sister and we would just support them the best way we could. We treated them like we would treat anybody within our home. We felt like we were really helping the community, helping these moms at a different level. We helped them not just medically, but emotionally as well.”

Zeman said her unit would often help provide prenatal care. “A lot of patients would just come in with no prenatal history at all and just like come in for a check. So, we would check things out for them and do all the tests, and make sure everything was okay and then encourage them to find a physician and help them find a physician.”

Of course, these burdens fall on communities already suffering health inequities. “We discovered that some communities, particularly those in rural areas with a higher percentage of Black residents and lower incomes, were more vulnerable to losing or not having OB services,” reported Katy Kozhimannil, the director of research for the University of Minnesota Rural Health Research Center. “The groups that already suffer the worst health burdens were most likely to lose hospital-based obstetric care.”

Kozhimannil’s research also found, perhaps not surprisingly, that the loss of hospital-based obstetric care increased the likelihood of preterm birth, which is the leading cause of infant mortality.

Kozhimannil is one of many public health policy researchers and experts who fear health outcomes could get much worse for women and other pregnant people after the Supreme Court overturned Roe v. Wade.

“I think we’re going to see a lot more emergency obstetric needs in rural communities that are not at all equipped to handle them,” she told Propublica in a May 4 article.

In an amicus brief filed on behalf of nearly 550 health policy professionals and three major health care policy organizations in connection with the Supreme Court case, the experts lay out the drastic consequences they foresee for people giving birth and children when access to abortion is drastically restricted.

“Women living in states with the most restrictive abortion policies … were found to be more likely to die while pregant or shortly thereafter than women living in states with less restrictive abortion polices.”

The authors of the amicus brief note that abortion bans “will disproportionately affect young women, women of color, and low-income women who live in families and communities already vulnerable to elevated health care and social risks and reduced access to necessary health care.”

As far as children born out of unintended pregnancies, the brief cites studies that indicate these children not only carry a high risk of preterm birth, low birthweight, and impaired development, but a higher risk for domestic violence, abuse, neglect, or other traumas as children.

“Where you live shouldn’t dictate the outcome of your pregnancy,” said Kozhimannil.

But in fact, many health care advocates and providers say that is indeed the case and they fear that as more labor and delivery units close, the situation will become even more critical, putting mothers and birthing people at risk.

And nurses know these closures don’t just affect the person giving birth; it adds stress and burden on entire families. If these patients or infants suffer complications in pregnancy and or during birth, those consequences can drastically alter the health of the entire family.

“Mothers and children are recognized worldwide as this very vulnerable community, who are at a really pivotal point in their lives, especially in regards to their health,” said Hovie. “So it just seems to make no sense that they would limit those services.”

Hovie said providing adequate care up front will reduce the need for more expensive care on the back end.

Professor McLemore said the people of the United States need to ask themselves if they really care about families. She said it is not only a question of who is making decisions about access to health care, but how we fail to support parents as a society.

“Birthing folks should be the revered holders of our species,” said McLemore. “It changes how we think about the people who have the courage to parent? It’s a really different narrative than saying, Oh, good luck, you had your baby at the hospital, we’re going to push you out, and oh, by the way, good luck with that. And we’re not going to give these things like paid family leave and all the other things that you need in order to be successful, or we’re going to extend your health coverage a year postpartum. Because we actually don’t really care if you live or die.”

Rachel Berger is a communications specialist at National Nurses United.