Don’t Try This At Home

The national hospital industry is peddling programs to treat acute-care patients in their residences, instead of in the hospital where they belong

By Rachel Berger and Lucia Hwang

National Nurse Magazine - January | February | March 2022 Issue

Fatmeh Kalaveras has spent almost 30 years as a bedside registered nurse and thought nothing could surprise her, but her hospital last year rolled out what until then was unimaginable to her: a nightmarish scheme to care for patients needing acute hospital care in their own houses.

“It is an insult to nurses, to the nursing and all medical professions, and even more worrisome, it is straight up dangerous for our patients,” said Kalaveras, who saw the program first hand when she worked as an emergency department nurse at Kaiser Permanente Medical Center in Vallejo, Calif.

These remote programs, what nurses are calling “Home All Alone” schemes, are aimed at keeping patients needing acute care out of the hospital. Instead of admitting these patients, who would otherwise be traditionally hospitalized, they are sent home with an iPad and a smartwatch to be “admitted” for “hospital care” at their home. The patient is told a team of medical professionals will monitor them remotely from a medical hub. These hubs could be many miles away, or even in a different state, from the patient. From the hub, “care teams” are sent out to check on the patient as the need arises. In cases where a provider needs to physically be with the patient, the remote team will then send out a nurse or what they are calling an “upskilled paramedic.”

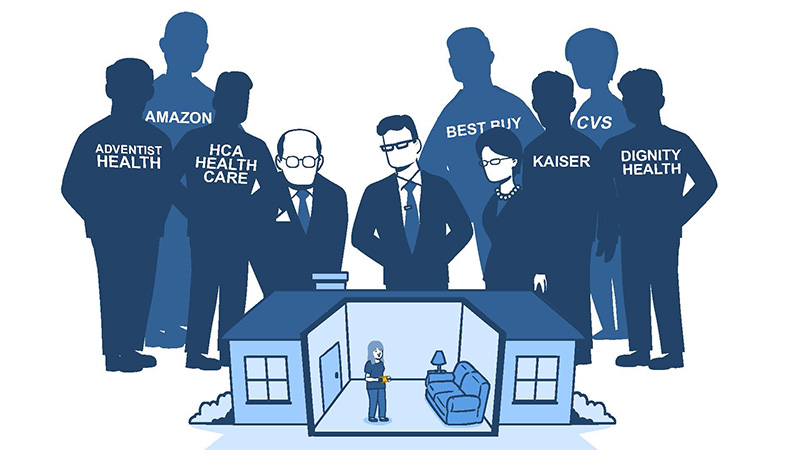

These Home All Alone schemes were born of an unholy alliance between a profit-driven hospital industry, technology giants, and venture capitalists seeking to reap profits by replacing hands-on skilled hospital care with robots, gadgets, and less-skilled contract workers.

“Labor is expensive and nurses have historically and continue to be undervalued for their professional expertise,” said Michelle Mahon, RN and assistant director of nursing practice for National Nurses United. “Hospital and health care executives have long pushed an agenda to cut labor costs by slashing nursing budgets. And now they are taking it a step further, by putting patients in a situation where they effectively have to care for themselves.”

While the hospital industry has for many years pushed to decentralize care away from the hospital and towards outpatient and telehealth programs, the pandemic provided an opening to promote, establish, and normalize these schemes on a much larger scale. In November 2020, as hospitals were overrun with Covid patients, the U.S. Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS) waived significant regulations governing the provision of hospital care, making it feasible for hospitals to send acute-care patients to their own homes but still collect as much in CMS reimbursements as if they were housed at the hospital.

Today, some 206 hospitals run by 92 systems in 34 states currently have temporary CMS waivers to run these Home All Alone programs. The list grows by the week.

“Nurses know that patients need us with them. Health care executives are trying to move us closer and closer to the day that medical professionals will no longer work in hospitals,” said Mahon. “Patients will only have gadgets, unlicensed personnel, and even lay people with minimal training providing their ‘care’ in outpatient settings. These Home All Alone schemes set us on the path to this dystopian and dangerous future.”

“It is an insult to nurses, to the nursing and all medical professions, and even more worrisome, it is straight up dangerous for our patients.”

The concept of treating acute-care patients in their homes is not new and some large hospital systems such as Mount Sinai Medical Center in New York and Johns Hopkins Medical Center in Maryland have been running a version of these programs for decades. But the federal government’s willingness during the Covid-19 pandemic to offer flexibility to hospitals to accommodate patient surges opened the floodgates to industry efforts to dramatically expand these programs and make such crisis standards permanent in pursuit of profit.

When the federal government declared a public health emergency (PHE) in March 2020, the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS) granted hospitals blanket waivers to treat patients through temporary expansion sites. But in November 2020, CMS expanded that waiver to allow hospitals to treat acute-care patients at home. Most importantly, it suspended the normal requirements under its conditions of participation to receive Medicare and Medicaid reimbursements for round-the-clock nursing care to be provided on site to patients, and for the immediate availability of a registered nurse.

According to a Dec. 7, 2021 New England Journal of Medicine Catalyst article, the “Acute Hospital Care at Home” program was developed with heavy input from industry players in just eight days. The waiver application form for “experienced” hospitals that have already treated 25 or more patients under such programs is literally two pages long. The waiver form for “inexperienced” hospitals is five pages long.

The program requirements shockingly lack in-person assessments of patients. After an initial in-person history and physical is taken of the patient by a doctor or advanced practice provider, there’s actually no requirement for any more in-person visits by a doctor or registered nurse. The program only requires two in-person visits per day, which can be fulfilled by an “MIH/CP,” which basically stands for a paramedic. Everything else is allowed to be done remotely, through telehealth visits and monitoring through technology and video. Only two vital sign readings need to be taken per day.

Most disturbingly, the program allows a 30-minute response time for patient emergencies, which can be met by calling the local 911 system. In a hospital, as nurses well know, providers can call codes and rapid response teams can be at a patient’s side with specialized equipment within seconds. There’s no comparison.

Elle Kruta is an RN at Mission Hospital in Asheville, N.C. She said when she first heard about these Home All Alone so-called “hospitalization” programs, she had a strong negative gut reaction.

“No, no, no, no, and no, some more,” said Kruta. “There is no substitute for human contact. You can feel the heat and cold of a person’s body, you learn so much from touching a patient’s abdomen. What does their breath smell like? Does it smell like juicy fruit gum? If so, you are already in trouble, you are in DKA [diabetic ketoacidosis].”

As long as hospitals met those minimal waiver conditions, they could bill and collect from CMS at exactly the same rates as if the patient were located at its brick-and-mortar hospital. CMS reimbursement is considered key to the viability of these programs, since the agency is such a significant payer of health care services and private payers often follow their rules. Without the guarantee that Medicare and Medicaid would pay for these kinds of programs, the hospital industry has little financial incentive to pursue them.

But the hospital industry views Home All Alone programs as a gold mine because it dramatically cuts one of their main overhead expenses: building, running, and maintaining physical hospital facilities. That’s why the industry has shelled out hundreds of millions of dollars to establish such programs.

“A very significant part of the expenses associated with hospitalization is fixed cost overhead, roughly 65 percent in most institutions,” said Stephen Parodi, MD, a Kaiser Permanente executive, during a May 2021 virtual press conference announcing Kaiser and Mayo Clinic’s $100 million investment in Medically Home, one of many companies springing up across the country that logistically supports these programs. “What if we move that patient to another site of care, where the overhead costs are much lower?” That site is, of course, the patient’s own home. But residential housing does not meet the same standards as a hospital facility, and lacks the backup power, water, and telecommunications infrastructure that’s critical in case of emergency.

These waivers exist, however, only because of the declared public health emergency and ostensibly would cease when it ends. That’s why the hospital and affiliated industries are lobbying heavily for either long-term extensions of these waivers or to make the waivers permanent. In addition to the American Hospital Association and state hospital association trade groups, the main players have started the Hospital at Home Users Group, an organization to promote and lobby for the deregulation needed to expand these programs.

In response to the industry’s incessant lobbying, lawmakers have proposed legislation at the federal and state levels to pave the way for these Home All Alone programs. For example, Wisconsin’s governor in March signed a bill eliminating the sunset date for such programs in that state, and in California, the state Assembly is considering a bill, AB 2092, that allows state hospitals to care for acute-care level patients in their homes as long as it has federal waiver approval and informs the California Department of Public Health (CDPH). Currently, hospitals that want to run such programs are required to apply to CDPH for the waivers of state regulations governing hospital care.

The hospital industry frames Home All Alone programs as the sunny future of hospital care. Hospitals tout all the reasons unrelated to actual health care outcomes as justification for these programs: Patients like being at home, patients can stay with their families and pets, patients may be at lower risk of nosocomial infections.

Nurses see it as simple patient dumping and depriving patients of our professional, 24/7 nursing care, with the most vulnerable, least-resourced, and often Black, Indigenous, Brown, and other patients of color and their households suffering the worst outcomes and perhaps death.

If these programs are allowed to grow, hospitals as we know them may ultimately disappear -- especially small-to-medium and more rural facilities. Already, overall hospital bed capacity nationwide is declining, dropping from 1.5 million in 1975 to about 919,000 in 2019, according to the American Hospital Association and Statista. And as more and more patients are sent home, hospitals will use the lower patient census as justification to close inpatient beds and further cut RN staffing, leading to a self-fueling death spiral of community hospitals. Brick-and-mortar rural hospitals, already an endangered species, will certainly go extinct.

“These programs are designed to make hospitals appear less relevant for our communities, and to make it easier to close down hospitals, especially those that don’t make money or serve patients who don’t have private insurance,” said Mahon. “If the pandemic has taught us anything at all, it is that we need more hospitals, and hospital beds, not fewer.”

According to the NEJM Catalyst article, hospitals treated only 1,878 patients as of Oct. 27, 2021 under the CMS waiver program, with 134 patients sent back to the brick-and-mortar hospital and eight unexpected mortalities. But market forces dictate that these programs must be adopted widely to make it worth the investment. Besides hospital systems themselves, private equity and venture capital firms have also invested in these schemes, seeing the possibility of huge windfalls. “We know these programs are not cheap to start,” said Mahon. “We know investors are chomping at the bit to see them expanded as quickly as possible and as widely as possible to recoup their investments and reap their profits.”

“There is no substitute for human contact. You can feel the heat and cold of a person’s body, you learn so much from touching a patient’s abdomen. What does their breath smell like? Does it smell like juicy fruit gum? If so, you are already in trouble.”

Nurses’ limited interactions with these fledgling Home All Alone programs already confirm that they are dangerous and untested for patients.

Kalaveras said she saw patients who were “admitted” to their homes, but “failed” and then returned to her ER far sicker than they had been originally. Her hospital, Kaiser Vallejo, is one of two pilot sites for Kaiser’s Advanced Care at Home initiative in Northern California and many more it’s operating in the Pacific Northwest,

“I have seen Covid patients who were sent home with an iPad return to the ER with their oxygen levels so low their lips were blue and they needed immediate lifesaving interventions,” said Kalaveras. “I cared for another patient who was returned to hospital by ambulance. His fever was through the roof, and he had a raging infection and was nearly septic.”

Kalaveras said she tried to convince that patient to remain in the hospital after he was given antibiotics and his fever was brought down. She told him she feared if he went back home, his fever could shoot back up and his condition could deteriorate quickly. But a nurse and a physician assistant, who were both contract workers with the remote program, convinced the patient to go home. The patient returned home by ambulance.

“I can only imagine the confusion a patient would feel when they are approached by a medical team, one wearing a white coat and so would easily be confused for a doctor, and that team is suggesting they return home, while a nurse is suggesting that they stay,” said Mahon. “There is no way the patient would know that the team is not part of the hospital staff.”

With no professional nursing staff available 24/7 in patient homes, the burden of care inevitably falls upon members of the patient’s immediate household -- mostly likely laypeople with no medical education, knowledge, or training.

Families often don’t realize how cumbersome and difficult patient care is, said Kruta, even when it is relatively simple. Kruta recalled teaching one family member how to care for a wound. “When we tried to explain how to do it, the caregiver puked,” she said.

“Families want to help their loved ones,” she added. They often feel unable to say they won’t or can’t provide the care. But then the reality of the task is often far more difficult than they had anticipated. Family members who may have promised to help with care start falling away. “After a week of it, the novelty wears off, and mama may have a pressure sore, or worse.”

Caring for a patient at home also puts enormous strain on the entire household, especially the caregivers who are very often the women. “We hear it all the time,” said Kruta. “They have a life, they have jobs, they have their own kids. They ask ‘How am I going to take care of them?’”

Data collected since the start of the pandemic shows clearly that women, and especially single mothers, suffer economic losses as their caregiving tasks increase. Nurses say it is easy to see how calling on families to care for loved ones who need hospitalization will lead to a disproportionate increase in economic losses for women.

In addition, nurses know the idea that family members can provide hospital-level care is absurd and unsafe. Registered nurses often serve as the last line of defense for patients against medical errors, especially in the area of medication administration. RNs are trained in the five rights when passing meds and discipline for medication errors can be severe. Yet hospitals, such as UC Irvine Medical Center in Irvine, Calif., write in documents submitted to the state health department supporting its Home All Alone program that patients and family/caregivers can give oral, subcutaneous, intramuscular, and even intravenous medications if they are assessed on their knowledge and skills. A remote nurse is supposed to watch over video when oral medications are given and document the medication administration in the record. Nurses are shocked by the nonexistent safety protocols for Home All Alone programs.

Nurses are particularly distressed about what will happen to Home All Alone patients when they code. A patient’s condition can go from bad to life threatening in just minutes.

In a hospital, patients in distress can access surgery, specialized medications, a rapid response team, and much more. But how fast will the medical cavalry come for a patient alone at home? Importantly, they ask, will there be someone who will even notice that the patient is decompensating?

Nurses know that sick patients are terrible at judging how ill they truly are, especially if they have altered cognition, as can happen with an infection and as a reaction to some medications, or illnesses.

“A lot of people just believe they are fine and people minimize what is happening,” said Genevieve Buttom, a registered nurse at Mercy General Hospital, in Sacramento, Calif. “I have seen a patient have a heart attack tell me they are fine. A lot of patients don’t want to be a burden, they don’t want to make a big deal.”

One Home All Alone program claims to have a fleet of vehicles with unspecified medical professionals who can arrive at a patient’s home “within an hour.” But nurses know that is entirely insufficient when dealing with an emergency.

“How long is it going to take to get a paramedic to them?” worries Joyce Ball, an emergency room nurse in Chicago. “It only takes one minute for a blood clot to travel to the heart and lungs, so that one minute is a matter of life and death.”

Perversely, marketers and hospital executives wrap these schemes in the language of racial and social equity, claiming they will expand health care to Black and Brown, poor, and rural communities. They claim that treating acute-care patients at home allows medical providers to enter people’s homes and address the social determinants of health that contribute to their illnesses, yet there’s nothing preventing health care corporations from tackling those problems now.

In reality, Home All Alone schemes pave the way for hospital closures, and will exacerbate socioeconomic and racial health inequities.

National Nurses United members say no to and urge their patients and the public to not participate in these programs. NNU is on a mission to educate its members and the public to understand how these Home All Alone programs destroy nursing, destroy hospitals, and destroy safe care for patients and communities.

On Nov. 10, 2021, Kaiser registered nurses across Northern California held more than 20 informational pickets to show their opposition to and warn the public about Kaiser’s and other hospital systems’ Home All Alone schemes. “Nurses and other health professionals cannot be replaced by iPads, monitors, and a camera,” said Deborah Burger, a president of NNU. “Our patients deserve much more than this and should flat-out reject Kaiser’s program. To send patients home and call that ‘hospital care’ debases what hospital care means, endangers patients, and is an insult to patients, nurses, and all the many health care professionals who provide care in hospital settings.”

NNU’s advocacy is already working. On April 5, Adventist Health and Rideout, which runs a hospital in the semi-rural community of Marysville, Calif., announced that it was pulling the plug on its Hospital@Home program after treating 194 patients over 15 months.

For nurses, this is an encouraging sign. “If someone needs to be hospitalized, they need to be in an actual hospital and under the care of highly skilled, educated medical professionals who are able to touch, assess, monitor, and respond to critical and emergent situations which can mean the difference between life and death,” said Burger. “These programs are a blatant attempt to increase profits by sacrificing high-quality patient care.”

Rachel Berger is a communications specialist at National Nurses United and Lucia Hwang is editor of National Nurse magazine.