The Opioid Crisis For Healthcare Workers

Opiates, including heroin, oxycodone, hydrocodone, codeine, morphine, and synthetic opioids, including fentanyl and carfentanil, have been implicated in the epidemic of opioid-related overdose deaths in the United States over the past few years. Between 2000 and 2015, more than half-a-million people died from a drug overdose in the United States. In 2016, about 145 people per day died from an opioid overdose.

Nurses can be exposed to opioids, including fentanyl and carfentanil, through contact with the patient, their environment, clothing, or linens. It is often unknown which opioid the patient was using and contamination may not be visible. Three nurses at an NNU facility were exposed to an opioid, that authorities believe was fentanyl or carfentanil, while providing patient care and cleaning a patient’s room. The exposure resulted in all three needing reversal with naloxone/narcan.

Employers must provide a safe workplace to all employees. Employers should create opioid exposure control plans with the input of direct-care registered nurses. This document details the elements that an employer’s exposure control plan should contain, including screening, isolation, and decontamination protocols, personal protective equipment, post-exposure follow up protocols, and training.

Nurse Exposure and Employer Prevention

Table of Contents

- Background Information

- Exposure Incidents

- Exposure Limits and Guidance

- Framework: Precautionary Principle

- Employer Responsibility

- Chemical Characteristics of Fentanyl and Carfentanil

- Nurses May be Exposed to Opioids When Providing Patient Care

- Employers Should Implement Protections to Prevent Occupational Exposure to Opioids to RNs

- Endnotes

Background Information

Opioids are a class of drugs that includes heroin, oxycodone, hydrocodone, codeine, morphine, and others. Fentanyl (fentanil, Duragesic®) and carfentanil (carfentanyl, Wildnil) and their analogues are potent opioids manufactured both legally and illegally. All of these have been implicated in the epidemic of opioid-related overdose deaths in the US over the past few years.i

Between 2000 and 2015 more than half a million people died from a drug overdose in the U.S. The number of overdose deaths involving opioids has quadrupled since 1999 while Americans report no overall change in pain.ii More than 53,000 people in the U.S. died from an opioid overdose in 2016—that is 145 people per day.iii Nearly half of these opioid overdose deaths involved prescription opioids, though recent data indicates that illicitly manufactured opioids are increasingly implicated.iv, v Synthetic opioid deaths, primarily related to illicitly manufactured fentanyl, increased 264% from 2012 to 2015.vi There are approximately thirty nonfatal opioid overdoses for every fatal overdose.vii

This rapid increase in opioid overdoses has led to increased healthcare use. Opioid-related emergency department visits in the U.S. increased by 99.4 percent between 2005 and 2014. The rate of inpatient adult hospital stays related to opioids increased 64.1 percent between 2005 and 2014.viii One retrospective cohort study of hospital discharge data in 44 states found a 34 percent increase in opioid overdose admissions to intensive care units between 2009 and 2015.ix

Some states and regions report higher rates of opioid-related deaths and law enforcement drug encounters than others. The Northeast and Midwest regions had the largest increases in total deaths involving heroin between 2010 and 2015 and the largest increases in total deaths involving synthetic opioids between 2013 and 2015.x Similarly, the largest increases in fentanyl drug reports by law enforcement from 2013 to 2015 were seen in the Northeast and Midwest regions.xi The rate of inpatient stays related to opioids varied by a factor of 5.6 across states in 2014. Of the 44 states and the District of Columbia included in the study, the highest opioid-related inpatient rates were in Maryland (403.8 stays per 10,000 population), Massachusetts (393.7 stays), and the District of Columbia (388.8 stays) and the lowest rates were in Iowa (72.7 stays per 10,000 population), Nebraska (78.6 stays), and Wyoming (96.7 stays).xii

Exposure Incidents

Several media reports have indicated that occupational exposures are occurring with negative and life-threatening impacts in several cases.xiii First responder personnel, including law enforcement and emergency medical transport, are the most commonly recognized groups with potential for occupational exposure to fentanyl and carfentanil and analogues. Many opioid overdose patients encountered by such first responder personnel may require emergency medical care and be transported to a hospital. Nurses providing care for opioid overdose patients in hospitals and other settings face potential for occupational exposure to fentanyl and carfentanil and analogues. Several exposure cases have been noted in the news media.

Exposure Limits and Guidance

There are no federal or consensus occupational exposure limits for fentanyl, carfentanil, or analogues. The National Institute for Occupational Safety and Health (NIOSH) has published guidelines for protecting emergency responder personnel who may be occupationally exposed to fentanyl, including during pre-hospital patient care, law enforcement, investigation and evidence handling, and special operations and decontamination. xiv Until recently, there was little recognition of the potential for harmful exposure to nurses and other healthcare workers when providing care to patients who had overdosed. In April 2018, NIOSH published guidelines for protecting nurses and other healthcare workers from potential exposure to fentanyl and its analogues.xv The NIOSH guidelines are missing key elements that are needed to be fully protective: the guidelines do not place clear responsibility on the employer to create and implement policies, work practice controls, personal protective equipment (PPE), and other elements; the guidelines do not incorporate the precautionary principle (see below) and therefore are not effective or implementable in many exposure scenarios; and the guidelines do not consider the risks posed by carfentanil, which is toxic in extremely small amounts, and therefore do not offer protection in situations where carfentanil may be present. While these guidelines fall short of the protections that nurses need, the agency’s recognition of potential hazardous exposure for nurses and other healthcare workers is significant.

Framework: Precautionary Principle

The precautionary principle holds that “action to reduce risk should not await scientific certainty.”xvi Recent events underline the ways that following the precautionary principle when making policy decisions would have led to better outcomes—Ebola epidemic and exposure and infection of nurses at Texas Presbyterian and repeated SARS outbreaks in Toronto. Regarding the opioid epidemic, there is limited scientific evidence specifying the exposure pathways and risks for nurses and other healthcare workers who provide care to patients recovering from an overdose. Very little is known about dosage, rate of metabolism, rate of elimination, and other pharmacokinetic properties of the drugs. But there is evidence that exposure to minute amounts of the most powerful opioids, fentanyl and carfentanil, can cause life-threatening symptoms and death. And so protections should be implemented in all situations where individuals may encounter even trace amounts of fentanyl/carfentanil. Application of the precautionary principle requires that healthcare employers should provide the highest level of protection to their employees until there is substantial evidence indicating different measures are appropriate.

Employer Responsibility

Under the Occupational Safety and Health Act of 1971, each employer is required to provide “to each of his employees employment and a place of employment which are free from recognized hazards that are causing or are likely to cause death or serious physical harm to his employees.”xvii Employers must address the life-threatening hazard posed by opioid exposure, especially fentanyl and carfentanil, to nurses and other healthcare workers who provide care to opioid-overdose patients.

Chemical Characteristics of Fentanyl and Carfentanil

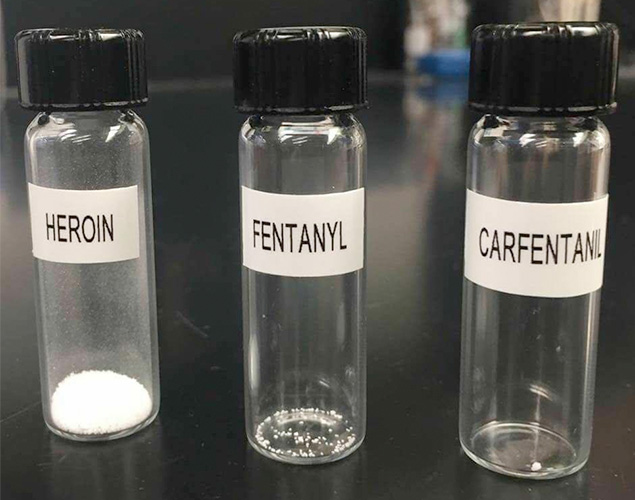

Fentanyl is manufactured commercially for pain control and anesthesia. Carfentanil is manufactured commercially only as a veterinary anesthetic for large animals. As a result, information on fentanyl is limited to specific therapeutic situations and very little is known about carfentanil in humans. Fentanyl and carfentanil are both manufactured legally and illegally but have not been studied extensively in off-label applications. The recommendations in this document therefore are based on the precautionary principle, utilizing the best available evidence. Fentanyl typically exists as a crystal or crystalline powder at room temperature, but may be dissolved into liquid solutions.xviii Precise dosage information is unavailable. Carfentanil is estimated to be 10,000 times as potent as morphine, 100 times as potent as fentanyl. Carfentanil activity in humans is estimated to start at about 1 microgram.xix This picture showing the lethal amounts of different opioids vividly illustrates their relative dangers, but each of them can be deadly (Figure 1).xx

Routes of Exposure to Opioids

- Individuals can be exposed to opioids, including fentanyl and carfentanil, through:xxi

- Inhalation of powder, crystals, or aerosolized droplets

- Ingestion or oral exposure to powder, crystals, or aerosolized droplets

- Skin contact and absorption, including through eye contact

- Needlestick injuries

Symptoms of Exposure to Opioids

Including Fentanyl and Carfentanil:xxii

- Miosis (contracted or pinpoint pupils)

- Reduced level of consciousness

- Reduced respiratory function

- Reduced blood oxygen content (blue lips may be observed in overdose patients)

- Accumulation of acid in the blood

- Low blood pressure

- Slow heart rate

- Shock

- Skeletal and thoracic muscle rigidity

- Slowing of muscular movement of the stomach with intestinal obstruction due to the lack of normal muscle function

- Accumulation of fluid in the lungs

- Lethargy

- Coma

- Death

Nurses May be Exposed to Opioids When Providing Patient Care

Nurses and other healthcare workers who provide care to opioid-overdose patients face exposure risk to the hazardous opioid drugs through patient bodily fluids and contamination of patient clothing and belongings. Exposure to fentanyl and carfentanil is of significant concern given the small amounts of exposure that can cause severe reactions and death.

Nursing personnel may encounter drug particles and residues on the patient’s body, clothing, and belongings. It may be very difficult to determine if a patient’s clothing and belongings are contaminated, especially while providing life-saving care. It is likely unknown which opioid or combination of substances the patient was using. Overdose patients may be discovered with drug paraphernalia in, on, and around their bodies.xxiv Given the potential for life-threatening reactions in response to extremely small exposures, it is most protective to assume the clothing and belongings of patients presenting with opioid overdose symptoms are contaminated with the drugs.

The presence of fentanyl and carfentanil in patients’ bodily fluids, including urine, presents an exposure risk for nursing personnel providing care. Fentanyl stays in the patient’s body and bodily fluids for a period of time. For IV fentanyl administration, one study reported that it took 72 hours for 75% of the original dose to be excreted in urine. Other factors may delay the body’s metabolism and/or elimination of the drug,such as liver and kidney damage,both of which are common in habitual drug users.xxv, xxvi Fentanylis metabolized primarily in the liver into metabolites with no opioid-receptor function. These metabolites are excreted in urine, with estimated 10% unchanged drug. The available data indicate that fentanyl is likely present inpatients’ urine and other bodily fluids for a period of at least a few days after overdose.xxvii This information is unknown for carfentanil in humans.

Employers Should Implement Protections to Prevent Occupational Exposure to Opioids to RNs

Employers of nurses and other healthcare workers providing care to opioid-overdose patients should create, implement, and maintain exposure control plans. These exposure control plans should be created with the input of direct care registered nurses. Employers’ exposure control plans should include, at a minimum, the following elements:

- Screening protocol to identify and isolate potential opioid overdose patients

- Personal protective equipment (PPE) should be made available to nurses and other healthcare workers who maybe exposed to opioids

- Decontamination and cleaning protocols

- Post-exposure follow-up

- Training

- Screening protocol to identify and isolate potential opioid overdose patients

Patients exhibiting signs and symptoms of opioid exposure and/or overdose should be assumed to be contaminated with the most potent opioid. There is often no way to know which opioid the individual used or how much they injected/ingested. It may be difficult to discern whether the patient’s clothing and belongings are contaminated with that drug. In order to effectively protect employees in all situations, employers should create a designated area for patients exhibiting signs and symptoms of opioid overdose to minimize potential contamination of the healthcare facility. The same level of protections should be implemented for every patient exhibiting the signs and symptoms of an opioid exposure until it can be determined otherwise.

- Personal protective equipment(PPE) should be made available to nurses and other healthcare workers to use when working in situation where exposure to opioids may occur. The PPE ensemble should include, at a minimum, the following:

- Respiratory protection

Respiratory protection should include either a NIOSH-approved elastomeric full-facepiece air-purifying respirator with multi-purpose N-, R-, or P-100 cartridges or a powered air-purifying respirator (PAPR) with high-efficiency particulate air (HEPA) filters.

Due to the potential for bodily fluid splashes while providing patient care, full-facepiece respirators or respirators with a hood should be used in healthcare settings. Because of the known potential for skin absorption of fentanyl/carfentanil, all skin surfaces should be covered by fluid-resistant or impermeable PPE while providing patient care. The combination of a half-facepiece respirator, e.g., N95, with goggles or a face shield is inadequate protection. Separate eye protection like goggles can interfere with the necessary seal of half-facepiece respirators and/or leave skin unprotected. A faceshield leaves skin susceptible to splash from below and may also interfere with the half-facepiece respirator seal. OSHA recommends that where eye protection is also needed a full-facepiece respirator should be utilized.xxviii Similarly, NIOSH’s 2004 Respirator Selection Logic indicates that where the contaminant is an eye irritant,“ a respirator equipped with a full facepiece, helmet, or hood is recommended.”xxix

Employers should verify that their respirator fit testing program is up-to-date and compliant with the OSHA Respiratory Protection Standard or other applicable standards. Where reusable respirators are implemented, a respirator maintenance program must be developed.

- Double gloves

Double gloves should be worn when providing patient care to an opioid overdose patient or handling any item that may have become contaminated with hazardous drug, including the patient’s clothing and belongings, and linen, equipment,and other objects in the patient’s hospital room.

Double gloves should be worn when providing care to opioid-overdose patients or handling any potentially contaminated item. The second pair of gloves provides better protection when doffing the PPE ensemble. The inner glove should be worn under the sleeve cuffs of the gown and the outer gloves should be worn over the sleeve cuffs of the gown.

- Fluid-resistant or impermeable coveralls and shoe covers

All skin and other clothing should be covered by a fluid-resistant or impermeable coveralls and shoe covers. Given the potential for skin absorption, it is important that employees be protected from all splashes, aerosolized drugs, and potential particulate contamination that may been countered while providing patient care or in the patient care environment. Coveralls should cover all exposed skin and clothing, including a hood or other head covering and fitting snugly at the ankles and wrists. Shoe covers should be worn to reduce the potential for transmission of hazardous drug particles to other areas of the healthcare facility. PPE donning and doffing procedures should be created and maintained to minimize the risk of exposure to the employee or contamination of the healthcare facility environment.

All PPE should be disposed of after use and kept separate for waste disposal that minimizes the risk for exposure to housekeeping and waste disposal workers and for contamination of other environments, similar to the waste disposal requirements for antineoplastic drugs. Hands should be washed with soap and water ONLY after removal of all PPE. Use of alcohol-based hand sanitizer may accelerate skin absorption of fentanyl and carfentanil.

- Respiratory protection

- Decontamination/Cleaning

Special care should be taken when employees are decontaminating and cleaning patient care areas after anopioid-overdose patient has been treated. Employers should develop decontamination and cleaning protocols that minimize potential for employee exposure to opioids and contamination of the healthcare facility.

The same PPE ensemble as described for providing patient care should also be used when cleaning the patient care area. Hands should be washed with soap and water ONLY after removal of all PPE. Use of alcohol-based hand sanitizer may accelerate skin absorption of fentanyl and carfentanil.

- Post-exposure follow-up

Naloxone should be maintained on all units where opioid overdose patients may be admitted for care or observation. Employers should develop protocols for administration of naloxone to employees whob egin to exhibit symptoms of opioid exposure while or after providing care to an opioid-overdose patient. All exposure incidents should be recorded and investigated as required under applicable OSHA and other standards. Problems discovered in employer’s exposure control plan during this investigation should be corrected. Employees who have been exposed to opioids and required administration of naloxone should be given time off to recover in a way that maintains the employee’s earnings, seniority, and all other employee rights and benefits, including the employee’s right to his or her former job status.

- Training

All nurses and other healthcare workers who may be expected to care for an opioid-overdose patient as part of their jobs should receive training, including at a minimum the following elements:

- A description of the opioid overdose epidemic in the U.S.

- How to recognize signs and symptoms of opioid exposure

- Appropriate administration of naloxone

- Description of the employer’s exposure control plan for opioids, including the employer’s identification and isolation procedures for potential opioid-overdose patients

- How employees can make concerns known or ask questions about this plan

- Description of the PPE ensemble needed to provide care safely to opioid-overdose patients

- How to don and doff the PPE ensemble

- How to maintain PPE

- How to properly dispose of PPE

- Limitations of PPE

- Hands-on practice donning and doffing the PPE ensemble

- When and how to seek medical help

Endnotes

- i — Fentanyl: Preventing Occupational Exposure to Emergency Responders.” [Online] Centers for Disease Control

and Prevention, Nov 28, 2016. Available at www.cdc.gov/niosh/topics/fentanyl/illegaluse.html (Accessed Sept

8, 2017). - ii — Opioid Overdose: Understanding the Epidemic.” [Online] Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, August

30, 2017. Available at www.cdc.gov/drugoverdose/epidemic/index.html (Accessed Sept 8, 2017). - iii — Provisional Counts of Drug Overdose Deaths, as of 8/6/2017.” Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

Available at www.cdc.gov/nchs/data/health_policy/monthly-drug-overdose-death-estimates.pdf (Accessed

Sept 8, 2017). - iv — Opioid Overdose.” Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, Sept 5, 2017.

Available at www.cdc.gov/drugoverdose/index.html (Accessed Sept 8, 2017). - v — Prescription Behavior Surveillance System: Issue Brief.” Centers for Disease Control and Prevention National

Center for Injury Prevention and Control, July 2017. Available at www.cdc.gov/drugoverdose/pdf/pbss/PBSS-Report-072017.pdf (Accessed Sept 8, 2017). - vi — Prescription Behavior Surveillance System: Issue Brief.” Centers for Disease Control and Prevention National

Center for Injury Prevention and Control, July 2017. Available at www.cdc.gov/drugoverdose/pdf/pbss/PBSS-Report-072017.pdf (Accessed Sept 8, 2017). - vii — Frazier, Winfred, Gerald Cochran, and Wei-Hsuan Lo-Ciganic. “Medication-Assisted Treatment and Opioid Use

Before and After Overdose in Pennsylvania Medicaid.” JAMA, Aug 22/29, 2017. jamanetwork.com/journals/

jama/article-abstract/2649173 - viii — Weiss, Audrey J., Anne Elixhauser, Marguerite L. Barrett, Claudia A. Steiner, Molly K. Bailey, and Lauren O’Malley.

“Statistical Brief #219: Opioid-Related Inpatient Stays and Emergency Department Visits by State, 2009-2014.”

Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality: Healthcare Cost and Utilization Project, Dec 2016. - ix — Stevens, Jennifer P., Michael J. Wall, Lena Novack, John Marshall, Dougals J. Hsu, and Michael D. Howell.

“The Critical Care Crisis of Opioid Overdoses in the United States.” Annals of the American Thoracic Society,

Article in Press, August 11, 2017. - x — Northeast region includes Connecticut, Maine, Massachusetts, New Hampshire, New Jersey, New York,

Pennsylvania, Rhode Island, and Vermont. Midwest region includes Illinois, Indiana, Iowa, Kansas, Michigan,

Minnesota, Missouri, Nebraska, North Dakota, Ohio, South Dakota, and Wisconsin. - xi — O’Donnell, Julie K., R. Matthew Gladden, and Puja Seth. “Trends in Deaths Involving Heroin and Synthetic

Opioids Excluding Methadone, and Law Enforcement Drug Product Reports, by Census Region–United States,

2006-2015.” MMWR 66(34); 897-903, Sept 1, 2017. - xii — Stevens, Jennifer P., Michael J. Wall, Lena Novack, John Marshall, Dougals J. Hsu, and Michael D. Howell.

“The Critical Care Crisis of Opioid Overdoses in the United States.” Annals of the American Thoracic Society,

Article in Press, August 11, 2017. - xiii — Affinity Hospital, Massillon, OH www.cantonrep.com/news/20170808/affinity-nurses-treated-after-exposure-to-unknown-substance

Stafford County, Virginia www.nbcwashington.com/news/local/

Stafford-County-Deputy-Nurse-Accidentally-Exposed-to-Dangerous-Opioid-438587163.html

Soin Medical Center, Beavercreek, OH, www.daytondailynews.com/news/crime--law/fairborn-paramedic-overdoses-driving-patient-hospital/7c4RC1Orm0h6gsx9ouyvrJ/?ref=cbTopWidget

Rhode Island, turnto10.com/news/local/unknown-substance-that-sickened-officers-in-warwick-identified - xiv — Fentanyl: Preventing Occupational Exposures to Emergency Responders.” National Institute for Occupational

Safety and Health. August 30, 2017. www.cdc.gov/niosh/topics/fentanyl/risk.html

(Accessed November 21, 2017). - xv — Fentanyl: Preventing Occupational Exposures to Healthcare Personnel in Hospital and Clinic Settings.” National

Institute for Occupational Safety and Health, April 23, 2018. Available at www.cdc.gov/niosh/topics/fentanyl/healthcareprevention.html (Accessed May 9, 2018). - xvi — Brosseau, Lisa M., and Rachael Jones. “COMMENTARY: Protecting health workers from airborne MERS-CoV—

learning from SARS.” Center for Infectious Disease Research and Policy, May 19, 2014. Available at www.cidrap.umn.edu/news-perspective/2014/05/commentary-protecting-health-workers-airborne-mers-cov-learning-sars

(Accessed Sept 8, 2017). - xvii — 29 USC 654(a)(1)

- xviii — PubChem Open Chemistry Database: Fentanyl.” National Institute of Health. Available at pubchem.ncbi.nlm.nih.

gov/compound/fentanyl#section=Top (Accessed Sept 8, 2017). - xix — Drugbank: Carfentanil.” Available at www.drugbank.ca/drugs/DB01535 (Accessed Sept 8, 2017).

- xx — Kensington Polic Service. Available at www.facebook.com/KtownPolice/photos/a.1816514231927239.1073741828.1816447628600566/1900009366911058/?type=3&theater

(Accessed Sept 8, 2017). - xxi — PubChem Open Chemistry Database: Fentanyl.” National Institute of Health. Available at pubchem.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/compound/fentanyl#section=Top (Accessed Sept 8, 2017).

- xxii — PubChem Open Chemistry Database: Fentanyl.” National Institute of Health. Available at pubchem.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/compound/fentanyl#section=Top (Accessed Sept 8, 2017).

- xxiii — PubChem Open Chemistry Database: Fentanyl.” National Institute of Health. Available at pubchem.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/compound/fentanyl#section=Top (Accessed Sept 8, 2017).

- xxiv — Sumner, Steven Allan, Melissa C. Mercado-Crespo, M. Bridget Spelke, Leonard Paulozzi, David E. Sugerman,

Susan D. Hillis, and Christina Stanley. “Use of Naloxone by Emergency Medical Services During Opioid Drug

Overdose Resuscitation Efforts.” Prehosp Emerg Care, Mar-Apr 2016, 22(2): 220-225. - xxv — Health Consequences of Drug Misuse: Liver Damage.” National Institutes of Health: National Institute on Drug Abuse. Available at www.drugabuse.gov/publications/health-consequences-drug-misuse/liver-damage

(Accessed Sept 8, 2017). - xxvi — Health Consequences of Drug Misuse: Kidney Damage.” National Institutes of Health: National Institute on Drug Abuse. Available at www.drugabuse.gov/publications/health-consequences-drug-misuse/kidney-damage

(Accessed Sept 8, 2017). - xxvii — Drugbank: Fentanyl.” Available at www.drugbank.ca/drugs/DB00813 (Accessed Sept 8, 2017).

- xxviii — OSHA Technical Manual: Respiratory Protection.” Occupational Safety and Health Administration. Available at www.osha.gov/dts/osta/otm/otm_viii/otm_viii_2.html (Accessed Sept 8, 2017).

Section VIII B. 2. “Corrective Glasses or Goggles. Corrective glasses or goggles, or other personal protective equipment, must be worn in such a way that they do not interfere with the seal of the facepiece to the face. Since eye glasses or goggles may interfere with the seal of half-facepieces, it is strongly recommended that full-facepiece respirators be worn where either corrective glasses or eye protection is required, since corrective lenses can be mounted inside a full-facepiece respirator. In addition, the full-facepiece respirator may be more comfortable, and less cumbersome, than the combination of a half-mask and chemical goggles. OSHA’s current standard on respiratory protection, unlike the previous one, allows the use of contact lenses with respirators where the wearer has successfully worn such lenses before.” - xxix — Bollinger, Nancy. “NIOSH Respirator Selection Logic.” National Institute for Occupational Safety and Health, 2004. Available at www.cdc.gov/niosh/docs/2005-100/default.html (Accessed Sept 5, 2017).