News

Sweet Charity: The Truth Behind Hospitals’ Community Benefits Windfall

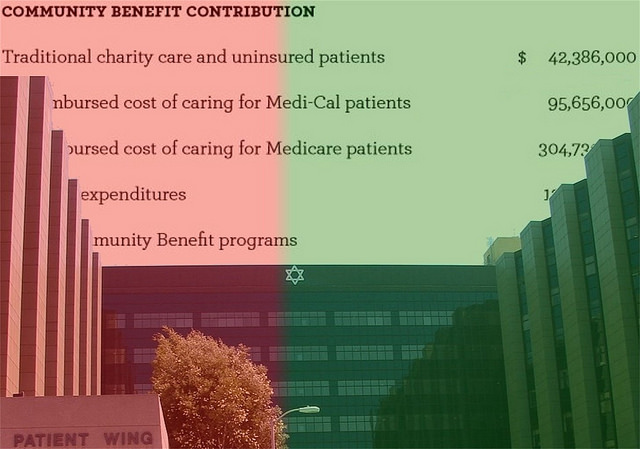

Every year Los Angeles’ Cedars-Sinai Medical Center releases a glossy brochure called Report to the Community. Among the doctor profiles and research-breakthrough stories are several dry metrics dealing with the number of beds, total patient and outpatient days and, perhaps most impressively, the year’s dollar value for something called “community benefit contributions.”

Cedars, which is the state’s third highest-earning nonprofit hospital, claimed $640.3 million as its 2012 community benefit contribution.

This number turns out to be the real point of the report. Because under state law all not-for-profit hospitals must justify their continuing tax exemption as charitable institutions by demonstrating that they are providing a community benefit — free charity care to indigent patients and what California calls “activities that are intended to address community needs and priorities primarily through disease prevention and improvement of health status.”

Whether Cedars and California’s other nonprofit hospitals have been living up to that charitable obligation is a question that Assembly Bill 503, currently under consideration in Sacramento, seeks to clarify.

It’s no trifling matter. In 2010 taxpayers spent an estimated $3.3 billion granting exemptions for the state’s nonprofit hospital industry, according to a 2012 report released by the Institute for Health and Socio-Economic Policy, the research arm of the California Nurses Association (CNA), which is also a financial supporter of Capital & Main.

The CNA study places Cedars at the top of its statewide list for hospitals receiving the most in tax exemptions beyond what they offer in actual charity care. For 2010, CNA calculated the value of Cedar’s charity care at only $16,123,766 and its tax exemptions in excess of charity care at $104,327,297. Industry-wide, the study said, the exemptions in excess of actual care totaled $1.8 billion.

AB 503 was introduced by Assemblymembers Bob Wieckowski (D-Fremont) and Rob Bonta (D-Oakland), and co-sponsored by the CNA, the Greenlining Institute and California Rural Legal Assistance (CRLA).

The legislation, its authors say, is an attempt to bring California’s community benefit law into line with federal rules, as well as to add what they maintain is a much needed level of transparency to the sometimes sketchy methodologies and liberal accounting practices tolerated under the current law.

“What happens,” Wieckowski told Capital & Main, “is that each of these nonprofit hospitals now sets their own valuation of what they think is their community benefit or their charity care. And they all use a different accounting of what they believe is the contribution. And the audits that have been done and the reviews have been saying, ‘Well, wait a minute. We should have some standardized [methodologies].’ If you give a vaccination to school kids, that vaccination within limits shouldn’t be $100 in San Diego and $10 in Sacramento, depending on the nonprofit hospital, right?”

According to Medicare cost reports, as of June, 2013, California hospitals rank third nationally in how high they set their charges over cost, on average billing $451 for every $100 of costs. Between 2006-2008 alone, the practice resulted in class action price-gouging settlements that returned nearly $1 billion to patients.

The difference paid by Medi-Cal and Medicare on the one hand, and, on the other, the much higher and often arbitrary and convoluted prices set by hospital chargemasters that are currently written off as charity care, is known as a public program shortfall. According to a report issued last year by the Greenlining Institute titledNot-for-Profit Hospitals and Community Benefit: What We Don’t Know Can Hurt Us, as well as a 2013 study in the New England Journal of Medicine, this shortfall is the top community benefit expenditure reported by hospitals.

Among other reforms, AB 503 will bring California into accord with the federal tax code, which disallows such shortfalls or accounts written off as bad debt to be classified as charity care.

“It basically tries to establish some standardized methodology for estimating what the economic value of community benefits are to a community,” says Wieckowski.

California’s hospital industry sees the bill differently. “There already is transparency,” insists California Hospital Association (CHA) spokesperson Jan Emerson about the present law. “The bill is completely unnecessary and is a rerun of a piece of legislation that was soundly defeated a year ago in the state Assembly — AB 975.”

California’s existing community benefit law was sponsored by CHA and the California Association of Catholic Hospitals in 1994 after a federal appeals court ruled that a Pennsylvania not-for-profit didn’t qualify for tax exempt status because it failed the federal tax code’s community benefit test.

But by excluding standardized definitions for either charity care or community benefit, and prohibiting the consideration of the dollar value of a nonprofit hospital’s community benefit plan when evaluating its tax-exempt status, the California law also gave the state’s nonprofit hospitals wide latitude in formulating their community benefit plans – and deciding what constitutes a community benefit in the first place.

Under present law, even the costs for producing Cedar’s slick promotional reports could be charged off by the hospital as community benefit. The problem, say advocates, is that reporting is so murky that it’s usually impossible to tell what is being written off.

“When we actually looked at what hospitals were defining as community benefit, it was very unclear,” says Carla Saporta, a co-author of the Greenlining community benefit study. “It’s just a black box. There isn’t a lot of transparency to what the hospitals are doing.”

At a time of noose-tight budgets that disproportionately impact low-income populations already prone to preventable conditions such as obesity, coronary heart disease, diabetes and lung cancer, underutilized community benefit dollars are increasingly being eyed as a public health resource that could patch California’s badly frayed public-health safety net.

“We would welcome more,” says Noe Paramo, a CRLA legislative advocate who specializes in health policy for the San Joaquin Valley’s farm worker communities, which were left out in the cold by both the Affordable Care Act and Covered California. According to CRLA estimates, 353,000 people — about nine percent of the eight Central Valley counties’ population – will either be denied health coverage or be unable to afford it. At the same time, Paramo says, these counties have been cutting funding for their indigent patient programs, with the exception of emergency care.

AB 503 is scheduled to come up before the Senate Health Committee June 25. Wieckowski is optimistic about its chances.

“We’ve made some changes [from AB 975]” he says. “I’ve narrowed the scope of the bill.

Nevertheless, the legislation will give the state, for the first time, a standard definition of charity care, as a direct provision of care rather than the promotional activities, marketing or cost containment that frequently go into the ledger as “community benefit.”

The bill will also require nonprofit hospitals to allocate a minimum of 25 percent of their community benefit budget to public health programming and ensure that the majority of any dollars spent on community benefits go to the state’s most vulnerable populations.

“What I’m trying to do is highlight that we give special status to this group of hospitals versus the other hospitals,” Wieckowski says. “And what we expect in return is that our local communities know what’s going on [to] determine if we are getting value for the tax benefit we are conferring to them.”