News

How the Cleveland Clinic grows healthier while its neighbors stay sick

The Clinic is a global success story, but its host community remains mired in poverty

CLEVELAND — On the Cleveland Clinic’s sprawling campus one day last year, the hospital’s brain trust sat in all-white rooms and under soaring ceilings, looking down on a park outside and planning the next expansion of the $8 billion health system. A level down, in the Clinic’s expansive alumni library, staff browsed century-old texts while exhausted doctors took naps in cubbies. And in the basement, a cutting-edge biorobotics lab was simulating how humans walk using a cyborg-like meld of metallic and cadaver parts.

And about a block away — and across the street that separates the Clinic from the surrounding Fairfax neighborhood — a woman named Shelley Wheeler was trying to reattach the front door of her house. She’d had a break-in the night before.

Wheeler has lived in the neighborhood for almost 50 years and seen it wither; her street is dotted by vacant lots and blighted homes. Infant mortality is almost three times the national average. But she’s also warily watched as one player continues to grow: The health system with gleaming towers that are visible from her front stoop.

“Cleveland Clinic is just eating everything up that they can,” she said, pointing to the 17-block stretch of land where the system has steadily expanded — to the frustration and protests of Wheeler and her neighbors.

“At some point, Cleveland Clinic is going to come” for her land, she added. “When, we don’t know. I’m trying to save my house,” Wheeler said — before excusing herself to meet with police investigating her break-in.

A view from the edge of campus shows how the Clinic marches up against the leafy neighborhood around it, and where its next expansions could be coming. (M. Scott Mahaskey/Politico)

There’s an uneasy relationship between the Clinic — the second-biggest employer in Ohio and one of the greatest hospitals in the world — and the community around it. Yes, the hospital is the pride of Cleveland, and its leaders readily tout reports that the Clinic delivers billions of dollars in value to the state. It’s even “attracting companies that will come and grow up around us,” said Toby Cosgrove, the longtime CEO, pointing to IBM’s decision to lease a building on the edge of campus. “That will be great [for] jobs and economic infusion in this area.”

But it’s also a tax-exempt organization that, like many hospitals, fought to preserve its not-for-profit status in the years leading up to the Affordable Care Act. As a result, it doesn’t have to pay tens of millions of dollars in taxes, but it is supposed to fulfill a loosely defined commitment to reinvest in its community.

That community is poor, unhealthy and — in the words of one national neighborhood-ranking website — “barely livable.”

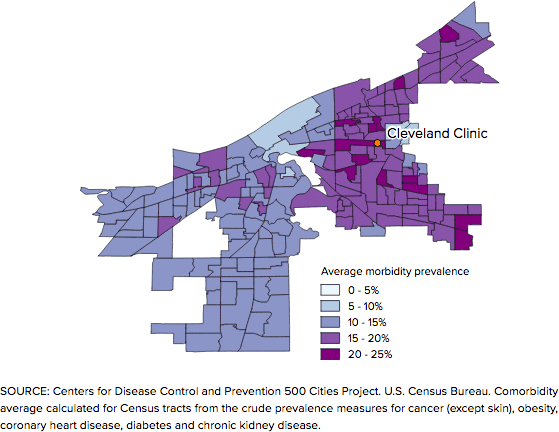

More than one-third of residents in the census tract around the Clinic have diabetes, the worst rate in the city, according to the latest data from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. That’s just one of numerous chronic and preventable health conditions plaguing the area around the Clinic. Meanwhile, neighborhood residents say there are too few jobs and talk of hearing gunfire every night.

It’s the paradox at the heart of the Cleveland Clinic, as it lures wealthy patients and expands into cities like London and Abu Dhabi. Its stated mission is to save lives. But it can’t save the neighborhood that continues to crumble around it.

The neighborhood

The area around the Cleveland Clinic’s main campus has higher rates of diseases such as coronary heart disease, cancer, diabetes and chronic kidney disease.

An oasis of prosperity

The local joke is that Cleveland’s economy is powered by its basketball team’s superstar LeBron James. But leaving the airport, the first billboard advertises the real engine of the city: its local hospitals. And no hospital is bigger, richer or more influential than the Cleveland Clinic — which was praised by both Mitt Romney and Barack Obama in their 2012 debates, a rare point of agreement between the candidates. (The Clinic took out full-page ads to celebrate.)

While Cleveland isn’t especially prosperous, the Clinic’s campus is a world apart, evoking an upscale resort or an airport’s international terminal — an alternate universe where smokers and fast-food restaurants are banned, where foreign-language speakers are numerous and where live music and farmers markets are frequent.

The streets of the Clinic’s 165-acre campus are smooth; the bike lanes paved; a 77-foot-wide fountain greets visitors outside the main lobby. The buildings are all sleek steel and glass — a deliberately white color scheme that resembles an Apple store. Guests can take tours to see the thousands of pieces of art dotting the rooms and walls, picked out by the Clinic’s three full-time curators. A spine of green parks wind between more than a dozen buildings. High-profile speakers like Facebook’s Sheryl Sandberg and Microsoft’s Satya Nadella drop by for televised conversations with Clinic CEO Cosgrove.

All the major buildings are connected by skyways, some of which feature flat-screen TVs that loop ads for the Clinic’s own services. A doctor on staff could spend years entirely inside this bubble, from parking in an adjacent garage every morning — where art prints from artists like Andy Warhol and Roy Lichtenstein hang in the corridors — to eating at the 24-hour Au Bon Pain, never setting foot on the sidewalks outside.

The beautiful, sheltered campus reflects decades of willful development, says Richey Piiparinen, who studies urban planning at Cleveland State University and says that the Clinic — like many big-city institutions — has deliberately walled itself off. “It’s divorced from the neighborhood. It’s [even] policed differently,” Piiparinen said, referencing the Clinic’s private force of 122 officers.

Step off campus, and the cracked sidewalks and trash welcome you to a different world; a dozen empty liquor bottles littered one half-block alone.

Just a few blocks from the Clinic’s high-end Intercontinental Hotel — where the flagship restaurant serves $49 steaks and $220 bottles of Dom Perignon — a McDonald’s sign announces $1 soft drinks. There are boarded-up buildings and weed-choked vacant lots. One store advertises bail bonds.

The population of the two neighborhoods that surround the Clinic — Fairfax and Hough, which are about 95 percent African-American — dwindled to 18,000 as of 2010, down from more than 38,000 in 1980 and more than 100,000 in 1960. There’s visible blight and houses with peeling paint. One fence was draped by an assortment of raggedy clothes, slowly getting soaked in a rainstorm. Unlike the Clinic just blocks away, there are no bike lanes.

And the poverty manifests in poor health outcomes, with the rate of preventable illnesses like chronic heart disease and high cholesterol well above the local and national averages. The Clinic’s own community assessment, published last year, ranked Fairfax and Hough as “highest need” possible in terms of health care access.

“You have one of the best global brands in health care, but some of the worst health care disparities” next door, Piiparinen said. “That’s the impact of not being connected to the neighborhoods.”

A climate of mistrust

It wasn’t always this way.

Almost a century ago, when the Cleveland Clinic set up shop on Euclid Avenue, the street was known as Millionaire’s Row. Industrialists like John Rockefeller and other elites made their homes on the boulevard. But the neighborhood turned over as taxes went up and wealthy residents fled to the suburbs. Today, there’s a very different millionaires row: The line of doctors’ luxury cars every morning, driving in from Cleveland’s suburbs in their high-end SUVs and even a few Teslas.

That daily traffic helped lead to a $331 million construction project called the Opportunity Corridor, a new three-mile highway that’s backed by the Clinic, run by the state transportation department and involves ripping up streets and tearing down dilapidated parts of town. (When asked about the project’s purpose, the Clinic’s top tour guide explained that the current road to campus “goes through neighborhoods that people don’t want to go through” and the Opportunity Corridor would help staff and patients get to the hospital faster.)

The construction project has been bogged down by controversy, however. A local councilman, T.J. Dow, temporarily blocked the project in early 2016, warning that the redevelopment wouldn’t benefit the residents of his community. The city later withheld millions of dollars in funding, saying the state wasn’t meeting its promised goals for minority hiring, before reaching a new deal last year.

Area residents circulate scare stories about the Clinic that are a mix of half-truths and outright myths. Several old churches in the neighborhood have burned down in recent years, and after the Clinic bought one newly vacant lot, some residents engaged in wild speculation — without any evidence — that the Clinic was responsible for the blaze. The Clinic has built power stations in the neighborhood that, despite no scientific proof, have alarmed locals who are worried about health risks.

That fear goes both ways: Even longtime Clinic leaders are uneasy about the neighborhood that they’ve spent years in. “I should’ve warned you: Don’t walk around here at night,” one 15-year executive advised.

Neighborhood residents are especially dismissive of the disproportionately white or foreign patients they see flock to the Clinic, suggesting that their presence is subtly gentrifying the neighborhood. A signature project by the local development corporation — which is backed in part by Clinic donations — was a large Middle Eastern market that’s a few blocks off campus and clearly intended for international customers. Over the course of four nights in an on-campus hotel last year — no matter the hour — as many as eight Middle Eastern men would sit around a table off the lobby, drinking tea and wearing garb that stood out in gloomy, rainy Cleveland. The hotel also offered subtle cues about who its best customers are; in the gym, there wasn’t a working channel showing the NCAA men’s basketball tournament, but there were nearly two dozen international channels, mostly in Arabic.

International patients are especially appealing to the Clinic and other top hospitals because they pay full fare — much more than the Medicaid rates for poor patients and a lot more than the fractional pay or charity care write-offs from treating the uninsured.

The campus’ expansion and seeming priorities aren’t lost on residents. One elderly African-American woman, a retired nurse who worked for decades in the city’s public hospital, said she’d talk about the Clinic only if I didn’t use her name. “You know what we call it?” she said, lowering her voice. “The plantation.”

“Cleveland Clinic and Toby Cosgrove really need to renegotiate their relationship with the black community,” said John Boyd, whose family has lived about two blocks away from campus since 1923 — and who says he’s scared to go to the Clinic for treatment. “[They’ve] been absolutely no benefit to the black community.”

Tensions break out

Those tensions spilled out at a community meeting in March 2016, as more than 100 black residents vented for hours about the Opportunity Corridor project.

The standing-room-only meeting — deliberately held in an events room at a local police station, Councilman Dow told the crowd, because previous meetings had been so rowdy — was framed as a chance to discuss the Opportunity Corridor’s effect on the community. Dow and two other black councilmen, Zack Reed and Jeffrey Johnson, stood at the front of the room — along with a pair of white out-of-town developers, who had projects tied to the corridor.

The atmosphere was heated from the opening moments, as some community members stood to harangue Dow, asking if he was holding up the project to seek side deals; others worried that the community was giving up valuable land for too little return.

But after a rough start, the councilmen began winning over the crowd after channeling their frustration toward the out-of-town developers and invoking the community’s distrust of the Clinic.

“I told Dr. Cosgrove, the people in my neighborhood don’t trust the Clinic,” Reed said, warning that the system’s vague promises of helping the community didn’t usually end well. “We the people of color, the poor people, get what I call the hot dog and beer jobs.”

“I said to Dr. Cosgrove, you got to take down that invisible wall,” Reed added. “If you only believe you can work across the street if you’ve got a medical degree, then it’s us against them … We’ve got to train people in the neighborhood to work there.”

“Now you’re talking,” a woman shouted from the crowd.

“We need a hand up, not a handout,” Dow added.

After the meeting, the councilmen acknowledged the difficult relationship between the city and its flagship institution.

“If there’s anything that Cleveland Clinic does for the neighborhood, it’s that they’re located in Cleveland — and everyone who works there pays taxes,” Johnson said. But the hospital doesn’t do enough to provide emergency care, he charged; unlike its neighbor University Hospitals, it’s not a Level 1 trauma center, and the Clinic was sued by the city in 2010 and again in 2011 for failing to provide sufficient services when it closed one of its hospitals in economically deprived East Cleveland.

That lawsuit was resolved, but some bad feelings still linger — along with the perception that the Clinic is more concerned with complex procedures that attract foreign patients than the well-being of its neighbors.

“You can come from the Mideast and get a heart, but you can’t run down there” for an emergency, Johnson complained. “There’s something fundamentally wrong with that.”

‘We have more than fulfilled our duties’

Clinic leaders see it differently – and not just about its commitment to the neighborhoods. The hospital that the Clinic closed in East Cleveland was replaced by a new community center that leaders tout as a “model of success.”

“We have three obligations,” Cosgrove told POLITICO in a nearly hourlong interview. “We need to provide great health care, we need to provide great jobs and we need to support education. And we have done all those three things.”

The Clinic is ranked second in the U.S. News & World Report hospital rankings, an ever-present point of pride around the campus and in its marketing materials. It employs nearly 50,000 people in Ohio, just a few hundred jobs behind the state’s top employer, Walmart. And it spends millions of dollars on its own physician education as well as making community investments, like partnering with a local high school on a fast-track health and science program.

The Clinic also has put $500,000 into a program to get rid of blighted homes in the neighborhood, Cosgrove said, and has channeled funds and support into the Fairfax Renaissance Development Corp., which is involved in job training and other community services.

“This particular area of town, 40 years ago, was way worse than it is now,” Cosgrove said.

One of the Clinic’s most significant community investments is in the Langston Hughes Community Health and Education Center, a facility that’s a mile from campus and which offers services like free exercise equipment, adult day care and even some primary care. It’s a hub for uninsured neighborhood residents to be steered toward health coverage, and patient navigators on staff said they end up directing about 90 percent of residents with medical needs to the Clinic. And it has devoted fans who say the center is one of the only safe places in the neighborhood.

“I wish we had more [services] like it,” said Juliet Jones, a retired nurse who lives two blocks away — and who carries a miniature baseball bat whenever she leaves her house, worried about community violence and drug dealers. Jones says she can barely sleep at night, hearing gunshots and prowlers. Nearly every lot on her street is vacant, including the house Jones owns next door; after repeated break-ins, her daughter moved out.

Donnell Ezell is another patron of the center and, in many ways, a clear Clinic success story: The former occupational therapy assistant worked for the Clinic for years and got thousands of dollars in financial assistance to help buy a home and move into the neighborhood. Now retired, Ezell uses the Langston Hughes center to exercise and help his daughter, who was born with special needs, and he speaks with pride about what the hospital has done for him; a Clinic-branded chair, emblazoned with his name, is prominently displayed in his living room.

But the question isn’t whether the Clinic is doing good things for the community, critics say. It’s whether it’s doing enough.

Juliet Jones, a retired nurse who lives in the neighborhood, picks up the miniature baseball bat she carries with her every time she leaves the house. (M. Scott Mahaskey/Politico)

Thanks to a loosely defined 50-year-old IRS regulation, the hospital is required to provide only “community benefit” in exchange for its tax exemption — no matter what those taxes would be worth. And in late 2013, three social advocacy groups concluded that the Clinic’s tax-exempt property in Cleveland was worth $1 billion, which meant the hospital was saving $35 million in annual property taxes alone. (The value of that property, and the forgone taxes, has only gone up since.) That money could go toward schools, roads and other city projects that desperately need funds, advocates say.

“It’s crazy to ask the everyday common person to invest in the city when you have these enormous nonprofits that aren’t,” said Scherhera Shearer, head of Common Good, one of the three advocacy groups, at the time.

But the clinic rebutted that report and has fiercely defended its tax-exempt status, successfully defeating regulators in 2014 after a decade-long battle when they attempted to strip property tax exemptions from a pair of satellite offices.

Cosgrove consistently argues that taxes would only worsen the financial pressures on hospitals like the Cleveland Clinic, and in his interview with POLITICO he pointed out that 23 percent of hospitals lost money last year. But that ignores that the Clinic isn’t one of them. Cosgrove’s hospital system cleared $514 million in profit last year and $2.7 billion the past four years, when accounting for investments and other sources of revenue.

And since the ACA coverage expansion took full effect, the Clinic’s been able to spend a lot less to cover uninsured patients; its annual charity care costs fell by $106 million from 2013 to 2015. But its annual community benefit spending only went up $41 million across the same two-year period, raising a $65 million question: Did the Clinic just pocket the difference in savings?

“I think we have more than fulfilled our duties,” Cosgrove said in response, pointing to the system’s total community benefit spending, which was $693 million in 2015. The majority of that spending, however, wasn’t free care or direct investments in community health; about $500 million, or more than 70 percent, represented either Medicaid underpayments — the gap between the Clinic’s official rate, which is usually higher than the rate insurers pay, and what Medicaid pays — or Clinic staffers’ own medical education.

Clinic leaders also argue that the hospital is a magnet that attracts talent and revenue to Ohio. The system calculated that its direct economic impact on Ohio in 2015 was $6.8 billion and its indirect economic impact was $5.8 billion.

“There are people like me who have moved to Cleveland to work for the Cleveland Clinic,” said Chief Financial Officer Steven Glass, who came to the system 15 years ago from Maryland-based MedStar.

“It’s not just how many people are employed at the Clinic,” Glass added. “When you’re drawing in world-renowned physicians, these are well-paying jobs in the community that then create [a] cascading effect.”

But community residents say those dollars are largely spent in other neighborhoods and they don’t see much trickle-down effect on their own; Glass himself lives in a suburb a half-hour away. “Other than fast-food chains, there’s nothing else around,” said Jones, the retired nurse.

Teenagers who live in the neighborhood and were interning at the Clinic said that’s where they want to work as adults; they were stumped about where they would work, if not at the Clinic. “Construction,” said one 14-year-old girl — gesturing to the hospital’s in-progress project across the street.

There’s also a perception problem, at best, with what the Clinic thinks it does for the community versus what it actually does. Several Clinic PR staffers suggested that Microsoft CEO Nadella’s interview with Cosgrove was an example of how the hospital opens itself up, with community members welcome to drop by. But the free tickets to the one-hour session had been pre-booked online well in advance, and the overflow room was packed by staffers wearing doctor’s coats and Cleveland Clinic badges. (Many neighborhood residents said they weren’t especially interested in the talk, and didn’t know who Nadella was.)

Several Clinic officials pointed to a weekly farmers market on campus as another service for the community, which lacks grocery stores. But the vendors at the market tell a different story, both in terms of their products — many of which are upscale conveniences like flowers or dog treats — and their clientele.

The customers at the market “are mostly doctors and nurses,” said one vendor operating a stand that sold wool and honey products. That account was confirmed by residents. “Too expensive,” said 76-year-old Betty Moise, who’s lived in the neighborhood for almost five decades.

How much more should be done?

One way the Clinic could make a difference, some activists say, is by working out what’s called a payment in lieu of taxes — essentially, keeping their valued tax-exempt status but making a partial contribution instead. Hospitals have struck deals to do so in Boston and other cities, but Cosgrove isn’t keen on the idea in Cleveland. “As soon as they start doing the same thing with the churches and the Salvation Army and the Red Cross and all the other tax-exempt organizations, we’d be happy to do our part,” he said.

The Clinic also could ramp up investments in out-of-hospital care and social supports, part of a movement toward what’s called population health — where fixing community problems like lead exposure and food deserts are viewed as equally important as treating heart attacks. There’s a financial incentive for doing it well: Hospitals that succeed at population health are being rewarded with higher payments from insurance companies and the federal government.

But Cosgrove hesitates on committing wholeheartedly to that idea, too. “That’s a good direction to go,” he allowed. “But how much can we do in population health?”

“We don’t get paid for this, we’re not trained to do this, and people are increasingly looking to us to deal with these sorts of situations,” Cosgrove added. “I say that society as a whole has to look at these circumstances and they can’t depend on just us.”

Job counselors say there’s one move the Clinic can easily make: Be more generous with its approach to neighborhood hiring. Deborah Copeland, who does workforce development and career coaching at Fairfax Renaissance Development Corp., says she’s seen community members get hired at the Clinic in entry-level jobs — and promptly fired because they didn’t fit in right away or had problems managing themselves in the workforce.

“They call all of their employees caregivers. And I like that,” Copeland said. “But all caregivers are not caregivers every day,” she added, saying it’s important to realize that “people come with a lot of baggage sometimes and need to be developed.”

Copeland says her team has helped a few dozen community members get jobs at the Clinic over the past few years — a step in the right direction. But given the generations of built-in poverty and the neighborhood’s deep disparities, experts say it’s like hoping a sand wall will hold back the tide.

“How do you [intentionally] break down the barriers, after they … built them up?” muses Piiparinen, the Cleveland State University researcher. “The two easiest ways to do it are have your employees live in the neighborhood, and have your tenured residents work in the anchor institutions themselves,” he offered — not easy to do when the neighborhood is so poor and the Clinic wants to hire highly skilled doctors, researchers and managers.

Piiparinen and others acknowledge that while the Clinic is investing off campus, it will take more investment and commitment — much more — to really reverse a decades-long trend. But the Clinic’s eyes are elsewhere. Its most visible projects and leaders’ excitement center on a new on-campus building that’s designed by Norman Foster — “the world’s leading architect,” as various staff members enthused — and its planned hospital in London, overlooking Buckingham Palace.

And more expansion in Cleveland is inevitable. In the hospital’s master planning room, tucked behind an unmarked door just steps from the main lobby, the footprints of the Mayo Clinic in Rochester, Minnesota, and Johns Hopkins in Baltimore are laid over maps of the Clinic, which dwarfs them. Those maps are a reminder, said a Clinic spokesman, that “our national rivals, Mayo Clinic [and Hopkins] … they don’t own the buildings around them, they have no place to grow but up.” In contrast, “we own much of the neighborhood around us and can really grow.”

There’s certainly plenty of opportunity, between the property the Clinic already owns and the empty patches that increasingly dot the neighborhood as it slowly dies. And that’s what folks like Moise, who moved to Cleveland in 1968 and sat with friends on a sidewalk, half-expect to see happen.

“I sat and watched them cut that field yesterday. The city cut it. It looks so pretty,” she said, gesturing to the vacant lot across the street, covered in grass. “But I often wondered … I might be dead and gone … I often wonder, what would they build there?”

Reporting for this story was supported by a grant from the Commonwealth Fund through the Association of Health Care Journalists.

Original Post: http://www.politico.com/interactives/2017/obamacare-cleveland-clinic-non-profit-hospital-taxes