Blog

I Was a Sudanese Refugee, Now Im an American Nurse

When patients wake up in the recovery room at Keck Hospital, University of Southern California, Tveen Kirkpatrick, RN, will be by their side, monitoring their transition from anesthesia back into clarity. It’s a new role for Kirkpatrick, who previously spent 10 years in the Neuro Intensive Care Unit—but navigating transitions is perhaps a natural fit for this nurse.

In the earliest years of her life, Kirkpatrick was a refugee.

“Growing up, I was always reminded how fortunate we are because their whole lives, my mom and dad had to deal with not feeling safe,” said Tveen, whose family is of Armenian descent. After fleeing the Armenian genocide in the early 1900s—her mother’s side of the family landed in Beirut, her father’s in Sudan. Her mother, by way of Egypt, eventually wound up in Sudan, as well, where she met Kirkpatrick’s medical student father, married and started a family.

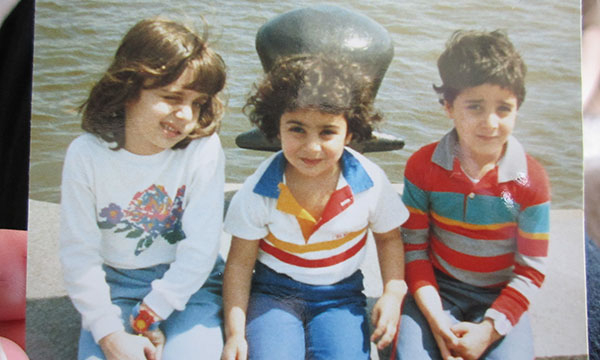

Kirkpatrick, the youngest child, was just one when civil unrest leading to the second Sudanese Civil War began in 1983. Her brother was two, her sister was four, and her parents—persecuted for practicing Christianity—feared for the family’s safety during the descent into a war that ultimately ended the lives of roughly two million people.

“We were so young to have to deal with that,” said Tveen. “They weren’t letting anyone leave.”

Her parents packed what they could and told authorities they were going on a two-week trip to visit a sick family member in America. Their lives in danger, Kirkpatrick’s family did not return to Sudan. Their journey toward political asylum lasted five years. During this time, they received deportation letters and had to stand before an immigration judge to explain that their lives were at stake—including relaying the story of a military raid on their house by Sudanese military with semi-automatic machine guns.

They were allowed to stay—a gift not taken for granted by a family who has returned the favor for their own lives being saved—by saving the lives of others. In addition to Kirkpatrick’s own work as an RN, her dad is a doctor, and her mother is also a nurse.

“My parents instilled such great values in us,” said Kirkpatrick. “When I was younger, we didn’t have a lot of money, and my dad got himself through medical school. I saw them struggle and how hard they worked. They were the examples of the American dream—the ability to pursue their passions and have ability to succeed. They were always giving gratitude to America and saying how great it was.”

Kirkpatrick became an official U.S. citizen at age 11 and followed what she said was “always my calling” to become a nurse. Her main passion has been integrative health—a mix of eastern and western approaches to caring for mind, body and spirit—and she currently chairs the Integrative Health council at Keck Hospital. She formerly chaired the quality and finance councils.

“My parents taught me to work hard, and to do everything to your full potential,” said Kirkpatrick.

This past weekend, as President Trump signed an Executive Order banning entry to the U.S. for people from seven predominantly Muslim countries, Kirkpatrick was struck by the echo of her own family’s story.

“When I saw Sudan was one of the countries listed, it really touched home,” she said. Along with her two-year-old daughter and husband, she responded to the news by heading to Los Angeles Airport (LAX), to join crowds of protestors.

“Being around that many people who were unified for common good, for human rights, felt so empowering,” said Kirkpatrick, who prays that the silver lining in all of this is that perhaps the current political climate has drawn people together in a new way that’s important for their personal growth—and for the evolution of a movement that can positively impact America’s future.

“Building walls, shutting doors and not letting refugees in, it’s really upsetting people right now. If anything, it’s building more hatred toward us on a global level,” said Kirkpatrick. “How are we being a good example if we’re saying ‘Your innocent children and wives need shelter—and we’re not going to give it to you’? If you provide people with shelter and love, and a place to raise their children, they have so much gratitude, and they will give so much back.”

“Right now, we are doing the reverse, and it’s really dangerous. The answer isn’t to drop bombs or shut people out, it’s to educate and show examples of love and kindness … America was founded on what the statue of Liberty says: ‘Give us your poor, give us your weak.’ It’s so sad that we’re changing the definition of that. These are people; they’re innocent.”

Kirkpatrick says her heart goes out to refugee families impacted by the travel ban, and she hopes they know there are “people out there who want to help them”—not the least of whom are nurses.

“Nurses, we’re such loving and powerful people, with who we are and what we stand for. Through unions like CNA bringing nurses together, we have a voice and the ability to bring change,” said Kirkpatrick. With the health and safety of refugees and immigrants on the line, she feels a trusted profession, dedicated to helping and healing all people—regardless of background—is a resonant voice.

“Every time nurses come together for something, we really have power.”

Read National Nurses United’s statement against the Muslim ban