Keeping up appearances

Magnet status is supposed to signify better staffing and working conditions for nurses, but RNs say it’s just a costly marketing tool that can’t compete with true empowerment through unionization.

By Lucy Diavolo

National Nurse Magazine - April | May | June 2023 Issue

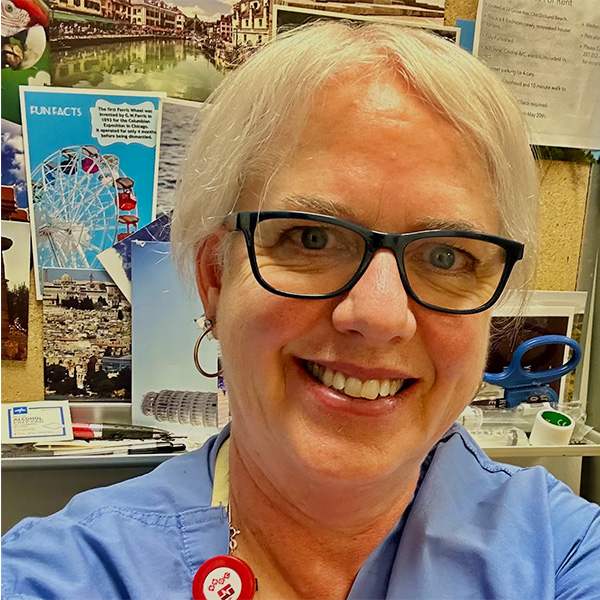

Everything you need to know about so-called “Magnet status” for hospitals can be summed up by the giant poster that hangs in the waiting room of Maine Medical Center, the state’s largest hospital. The poster, which features various assistant vice presidents cheering in an auditorium amid streamers and confetti, was put up last winter by management in self-congratulation for the facility maintaining its Magnet designation. But Amy Strum, an RN who has worked there for 33 years, said that the decoration was a lot more trouble than it was worth, both literally and figuratively.

“There was someone from maintenance told to put up this poster board touting our Magnet achievements in the middle of our crowded waiting room, where there was no room for it, so they actually moved people around in the waiting room to put this thing up,” Strum said.

To nurses, the poster serves simply as window dressing to cover up the serious staffing and patient care problems that being a Magnet facility failed to correct. “I’m not really sure even what Magnet means,” Strum said. “I haven’t noticed any change in anything, in so far as what it does for nurses or patients or anything.”

Magnet designation is an entire system ostensibly designed to recognize facilities with good working conditions for nurses, all in the name of addressing staffing. Back in the 1980s, nurse researchers connected to the American Nurses Association (ANA) studied a handful of hospitals (mostly academic, teaching facilities) that were renowned for their nursing care to better understand what made them special. The answers were common sense: excellent ratios of RNs to patients; respect and value for RN judgment, autonomy, practice; investment in RN staff, and more. But instead of advocating for their findings to be adopted by the hospital industry, the ANA’s response was to turn its research into a product by creating the Magnet Recognition Program, which is run by the American Nurses Credentialing Center (ANCC), a subsidiary of the ANA. Today, this certification system continues to be a big deal for hospital executives, as it’s supposed to be an apparent marker of a facility’s commitment to its nursing staff and high-quality medical care. Think of it like a Good Housekeeping Seal of Approval for hospitals.

And the program is even spreading internationally, as the ANCC continues to look for new customers abroad. Hospitals in the United Kingdom and Europe, Asia, and elsewhere are starting to seek Magnet accreditation.

But NNU nurses at Magnet facilities say the program is not all it’s cracked up to be. Instead of being a reliable sign that a facility treats nurses well, Magnet has become a “farce” that co-opts nurses’ existing organizing, gives them little input on the process, costs millions of dollars to maintain, is primarily a marketing tool for management, and has created cottage industries of “Magnet coordinator” nursing executives and Magnet-obsessed nursing schools eager to milk students for every penny. A 2010 University of Maryland School of Nursing study found that nurses at Magnet hospitals did not have better working conditions than nurses at non-Magnet hospitals, and a 2015 systematic review of the Magnet literature found that it was not possible from the available research to conclude whether Magnet accreditation had an effect on nurse and patient outcomes.

Moreover, the nurses National Nurse spoke to said that every good thing that Magnet promises nurses can actually be delivered — with transparency and accountability — by unionizing.

“I think that people don’t understand [Magnet’s] really not about nurses and patients,” said Lindsay Spinney, an RN at the newly unionized Ascension Seton Medical Center Austin in Texas, a Magnet-recognized facility. “It’s really about executives, and it’s really about the employer. It’s a marketing tool, and there’s a massive lack of transparency in what it is. I think when there’s a lack of transparency, it tends to mean there’s some issues behind the curtain.”

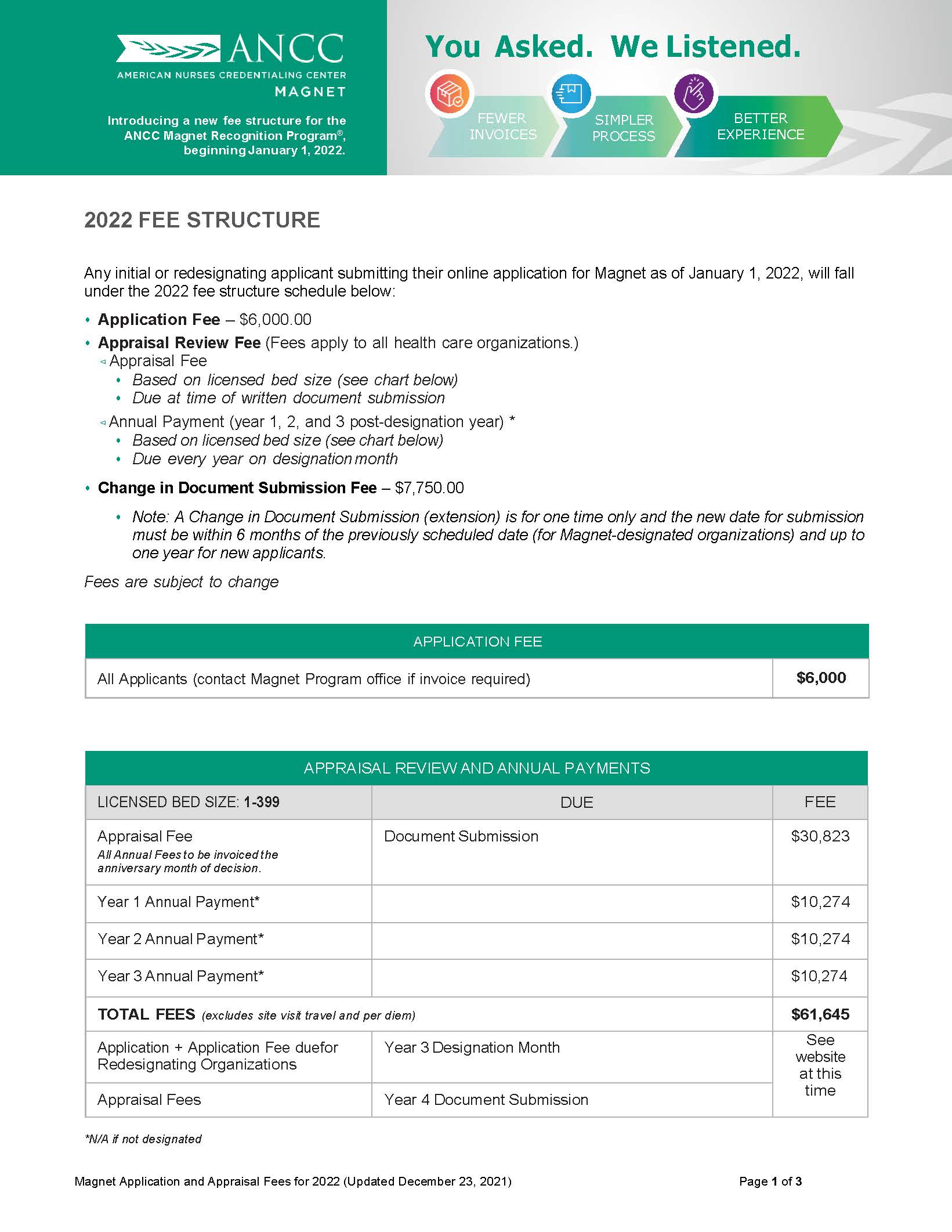

For this great honor of calling itself a Magnet facility, hospitals are willing to spend incredible sums of money -- often millions of dollars.

According to the ANCC’s website, for 2022, application fees and annual payments can range from roughly $60,000 to more than $120,000, depending on the size of the facility. And that’s only for a single three-year period of Magnet accreditation. In the fourth year of each cycle, facilities must reapply and spend more on the next application and appraisal. On top of that, there are additional premiums for multi-facility systems.

Meanwhile, as the ANCC website notes, fees are “subject to change” and applicants are advised to check prices at the time of their application for the current costs. But don’t worry — for just $335, you can get the official 2023 ANCC Magnet® Application Manual.

Beyond that, hospitals may also pay for Magnet appraisers’ travel, lodging, and per diem expenses as they appraise a facility, let alone the other things that management might spend on to bolster their case for Magnet or celebrate a win. Research conducted by the Robert Wood Johnson Foundation has put the total cost of the “Magnet journey” for a hospital at up to $2 million.

So why would hospital systems shell out for Magnet? As you probably guessed, the answer is money, but not in the traditional way that you might think. Some people think Magnet status helps attract more patients as customers, and it might on some level. But Magnet’s real money value lies in providing hospitals cover as a form of “faux staffing regulation” that they can claim they are following instead of being subject to real, enforceable safe staffing standards imposed by law through the government. Hospitals use Magnet designation as an excuse to oppose safe staffing ratios by asserting that they are already engaged in a form of “self-regulation,” an argument echoed by the ANA and its spin-off nursing groups -- all of which are opposed to staffing ratio laws.

“Nurses should be wary of anything that a corporate hospital is trying so hard to achieve because it’s not for the nurses. The bottom line is it will make them more money, one way or another,” said Strum, the Maine Med RN. “It has nothing to do with nurses or patients, it’s the pocket. You follow the money, and that’s where it goes. It goes into their pocket.”

Spinney, the Texas RN, has seen similar strategies from management to tout her facility’s Magnet status. But the giant posters don’t come without a sense of irony.

“We have huge banners,” Spinney told National Nurse, noting the banners have stayed up even through construction projects at the facility. “People are spending 12 or more hours in our emergency department walking around a giant Magnet banner. It’s vertical. It’s super tall. The irony is not lost on me.”

“I don’t think many people aside from management or administration had appreciation for Magnet,” Spinney said. “People thought it was kind of a joke. Especially at the end of 2020 with everything that happened and continued to happen beyond that, it was apparent to people not even really union-oriented, it’s kind of a farce.”

On the other side of the country from Maine, a similar story unfolded recently at Kaiser Permanente Los Angeles Medical Center (LAMC) when the facility achieved Magnet status in 2022. Tinny Abogado, RN, works in the step-down unit there and is a California Nurses Association (CNA) board member. She remembers previous, unsuccessful attempts to get Magnet at the facility and how it seemed to consume management’s focus. Because of the focus on Magnet, Abogado said, the union nurses’ concerns about issues like staffing or anything unrelated to Magnet were cast aside as management chased the credential.

“Every time we got a new chief nurse executive, Magnet was the first thing on their agenda,” Abogado told National Nurse. “The last one before the current one we have, she was pushing really hard for it, and there were rumors going around that, if she didn’t get it, they would replace her. And as soon as she got it, she left. It was as if that was the only thing she wanted to achieve at LAMC.”

The Magnet system has created its own labor market for nursing executives focused on getting hospitals recognized through the program. On the ANCC website, it’s clear that a chief nursing officer’s résumé or CV is considered a “supportive document” for Magnet applicants, so it makes sense people would build their careers upon successfully attaining Magnet status. As a 2022 article in the Journal of Nursing Administration titled “The Business Case for Magnet® Designation” puts it, “Creating a business case to secure the resources required to embark and travel on the Magnet journey is an essential tool for the chief nurse.”

Recent job openings for “Magnet coordinators” are seeking exactly that for Dell Seton Medical Center in Austin, Texas, and for Kaiser’s Northern California region, which appears poised to make a major Magnet push. Like the nursing executives Abogado saw at LAMC, people in these positions are focused on that one goal only and, once achieved, quickly parlay that job into one at the next facility desperate for Magnet status. Spinney, the Texas RN, has seen a similar revolving-door effect for Magnet-focused nursing executives. It’s clear that these nurse executives did not stick around long enough or even care to help the nursing staff solve systemic nursing problems at their facilities.

“Our CNO left almost as soon as they got Magnet,” she said. “It was shocking because everybody had worked so hard to get Magnet for her and done all this work for her, and she gave a very short amount of notice and then left to go to a different hospital in Houston.”

Part of the Magnet process involves the ANCC soliciting input from nurses at the facility. But Abogado said management would try to make sure they heard only from pro-Magnet nurses and that other nurses’ efforts to reach out to the ANCC and ANA directly went unanswered.

“There were signs in the breakroom saying, ‘You can email us anonymously to tell us about your facility,’” she explained. “Many of us did! We wrote to them and said, ‘LAMC is not ready for Magnet, we’re not even staffed right.’ And they went nowhere. They didn’t even answer us or even acknowledge they received our email.”

Strum said union nurses at Maine Med were similarly frustrated by feeling like they were excluded from the Magnet appraisal process. In their breakroom, pro-union nurses attempted to get involved with the appraisers, but found them elusive, a stark contrast from how nurses in management outside the bargaining unit were treated during the process.

“I don’t think it really matters when they walk through and talk to nurses,” Strum said. “A lot of union nurses were going into the breakroom to try and be in the conversation, and they would just move to a different place so the union nurses wouldn’t be there. It was very obvious that they were only trying to get one side of the story.”

For Spinney in Texas, the Magnet process at her facility was frustrating because many of the ideas and organizations nurses had originated to support one another were co-opted by management to look good for the Magnet application and appraisal process. She said a local interfacility nursing congress, a night shift council, and a new grad mentoring program all went from nurse-organized initiatives to projects management co-opted for the sake of Magnet.

“I am a night shift nurse. I’ve only ever worked the night shift,” Spinney said, explaining why she was part of a “night shift council” (NSC) of nocturnal RNs at her facility. That council helped night shift nurses plug into meetings they might miss during the day or advocate for themselves when, as Spinney put it, “Even administrators seem to forget we’re a 24-hour facility.”

“I was excited and voted for forming something like NSC, and upper management quickly realized that was something they could use for their Magnet application,” Spinney explained. “It started out great, but as soon as we got Magnet status, they dissolved the council within months. That is the kind of pattern I see over and over.”

The same thing happened with their local nursing congress, which was a body that had representatives from every unit of every Ascension facility in the region. Originally a “robust” network sharing knowledge and information, management once again decided it would look good for Magnet and got involved. In Spinney’s eyes, they ran it into the ground.

“It was a really great way to collaborate across the network and talk about nursing practice and evidence-based stuff,” Spinney said. “I was so impressed with nurses’ problem solving, working together, and having an open forum where you wouldn’t be retaliated against or judged for asking a question.”

“It was a really robust meeting up until about 2017, and Ascension started changing the way the administrators and executives were involved in things and got really involved,” she said, explaining that the meetings “immediately” started to disintegrate as a result. “They were trying to get insight for marketing strategies, which is the opposite of what that council was designed for.”

Another example for Spinney came in a mentoring program she helped launch. Originally conceived as a way to help new grad nurses acclimate to working in hospital settings, it was co-opted by a hospital educator. After that, Spinney said, it was touted in their Magnet appraisal process.

Programs like new-hire mentorships are a great way to help just-hired nurses integrate into a hospital and a community. Situations like what happened at Spinney’s hospital in Austin are troubling evidence in a pattern that, despite all the pomp and circumstance, the Magnet program might not even be helping staff nurse retention. In fact, it could be hurting it.

Now that LAMC is Magnet, Abogado said the designation hasn’t helped nursing staff retention at all. In fact, it may be harming retention. Because of the Magnet program’s focus on BSN nurses, BSN new grads get high priority in hiring. It’s such a big deal that the numbers of BSN and ADN nurses are tracked publicly in each unit. Despite this, turnover remains high and attrition might actually be exacerbated by the emphasis on more advanced education, as Abogado said these types of new grads often don’t remain at the bedside for long.

“All the new grads are BSN, some even MSN. We don’t have any ADN [new hires] anymore,” she said. “When they start out as BSN, in my experience, they often leave the bedside.” Abogado said that the trend is for nurses with bachelor’s and advanced degrees to move into management positions or quickly return to school for an even higher degree, such as nurse practitioner.

“I’ve been a bedside nurse for 25 years this year. Those who’ve been at the bedside long enough know it doesn’t matter if you have a Ph.D,” Abogado continued. “You don’t really accumulate knowledge until the day you start working as a bedside nurse. You can put a Ph.D nurse and an experienced ADN nurse in that room, and if I’m the patient, I want the ADN nurse.”

Given that BSN nurses are so prized in the Magnet system, it’s no surprise that a simple Google search for “What is Magnet status?” turns up results full of glowing praise from nursing schools eager to convince prospective students that earning a BSN makes them more likely to get a job in a Magnet facility. That way, just like Magnet Coordinators on the job market, nursing schools can cash in on the ANCC’s program. In the process, nurses whose life circumstances and bank accounts don’t allow them to pursue four-year programs or advanced, accelerated degrees remain disempowered and disadvantaged in the labor market.

Spinney in Texas said she’s also seen high turnover with BSN new hires. Like the posters celebrating Magnet status, it’s another irony of the Magnet program: while it’s ostensibly about nursing retention, it incentivizes hospitals to hire nurses who may be more interested in what comes after the bedside.

“All the BSN new hires already have a career path and are not spending much time bedside. They’re checking that box for experience and moving on,” she said. “Some of the best nurses do not have BSNs. They are the ADNs.”

To be sure, the nursing profession is experiencing a retention and staffing crisis. The aims of respecting and prioritizing registered nursing care are worthy ones. But NNU nurses we spoke to made clear that unions are the way to actually accomplish the goals Magnet claims to strive for. While Magnet talks a big game about empowering nurses, there’s no teeth to back it up the way there is when RNs exercise their union rights.

When Maine Med first began its Magnet campaign around 2000, the nurses had just waged an unsuccessful unionizing drive. To Strum, the timing was anything but coincidental. When Maine Med finally attained Magnet status in 2006, she remembers, “We might’ve got a free coffee or something, but I don’t think we even got a pizza party, to tell you the truth. Probably, we didn’t get our breaks that day, like any other day.”

Nothing changed until more than 20 years later, when the Maine Med nurses finally won their union and their first contract, genuinely creating major improvements at the facility.

At LAMC, Abogado said she can see the stark difference between authentic nurse-controlled bodies and for-show Magnet groups when she compares her union’s Professional Practice Committee (PPC) with management’s Unit-Based Committees (UBCs).

“In the UBC, [management’s] still in charge. They tell you to fill out this form, do this, do that,” she said. “But with the PPC, we have a voice. It’s more like 50-50. We don’t have to listen to you, and nurses can bring up our own issues. And those issues are relevant because we’re the ones at the bedside.”

For Spinney in Texas, even though they’re still fighting for a first contract, the union campaign has already produced major wins that never would’ve been possible through Magnet. Nurses have successfully pushed back on a policy mandating employees could only pick up prescriptions at company pharmacies, and they’ve fought to ensure nurses are only called upon to precept other nurses when they have a proper amount of experience to do so, as being forced to precept was driving nurses away from the facility.

Given what she’s seen, Spinney had words of wisdom for nurses at facilities seeking Magnet designation, saying, “Spend your time organizing. Spend your time doing anything else besides working on that.”

Strum from Maine Med was similarly vocal in advocating for unions before Magnet.

“If you’re not sitting at the table with management making decisions, then it will be unilaterally made by management, and nurses’ opinion and nursing is just going to be dragged along,” Strum told National Nurse. “Magnet does not give you a say in it. It doesn’t put you at the table. You cannot negotiate a contract with Magnet. You can’t strike. You can’t do anything.”

“Unions are the only way,” she said.

Lucy Diavolo is a communications specialist with National Nurses United.