Into the Mind

Learn what NNU nurses working in behavioral health across the country during Covid have observed, and how they are advocating for their patients.

By Chuleenan Svetvilas

National Nurse Magazine - July | Aug | Sept 2022 Issue

It takes almost five hours to drive from the western border of Los Angeles County to the eastern border of San Bernardino County. And that’s without traffic.

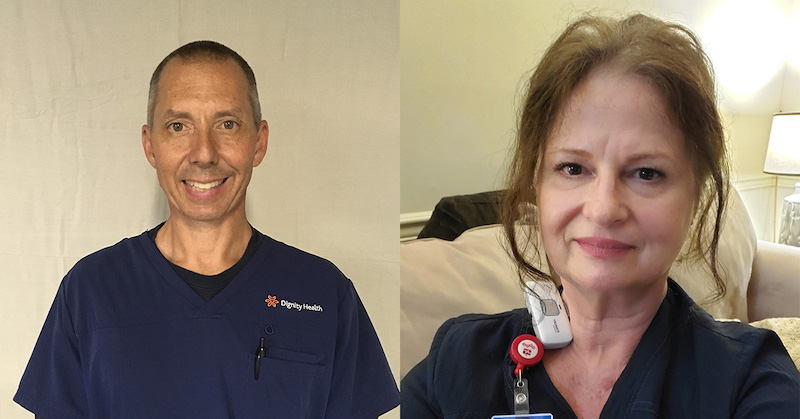

Those are the kinds of challenging circumstances Ron Weiss, an RN who cares for adult behavioral health unit (BHU) patients at Glendale Memorial Hospital in Glendale, Calif., worries about these days for his psych patients and their loved ones. “There are [no longer] many hospitals that have a psychiatric unit as one of their specialties, which limits the access of care in their communities, especially for children who are sent very far away from home, sometimes two counties away,” said Weiss. Family support is of critical importance for patients trying to recover from behavioral health problems. How are they supposed to do that when it takes an entire day of driving to even visit?

In Sacramento, Calif., more than 375 miles north of Glendale, psychiatric RN Laura Dixon’s latency and adolescent inpatients at Sutter Center for Psychiatry hail from as far north as Yreka, a small town near the Oregon border and as far south as Los Angeles, a nearly 7-hour drive from Sacramento or a 1.5-hour nonstop flight from LAX.

And Linda Rucker’s behavioral health patients at Jackson Park Hospital are primarily Black, Latinx, and Polish, and from the South Side of Chicago. But she is seeing transfers from other hospitals coming from as far as 60 miles away.

Long before the Covid-19 pandemic hit, mental health in the United States was already in crisis. Covid simply made the situation much, much worse. Patients placed at extreme physical distances away from their homes due to lack of BHU beds in their communities is just one symptom of the dire lack of inpatient care for behavioral health nationwide. Nurses reported many more stories about how our current money-driven health system is utterly failing patients who need inpatient mental health care and impeding nurses’ ability to provide it, but also shared how they enjoy and remain deeply committed to their work.

Behavioral health, mental health, and psychiatric nurses are on the front lines of this crisis every day. They see the impact of our profit-driven health care system on their patients, which results in delays in care, lack of available treatment for uninsured and underinsured patients, the closure of BHUs, little to no follow-up care after discharge, patients staying long-term in emergency departments or discharged with no place to go, and more. They also see how stigma against people with mental illness persists at all levels, resulting in missed care, intentional or unintentional discrimination by organizations and government agencies, dwindling services, and reluctance to seek treatment.

“What really catches my heart is that these patients are the most misunderstood patients that we have,” said Rucker, a behavioral health RN in the emergency department at Jackson Park Hospital in Chicago since 1996. “These are patients with illnesses. They are not completely aware of what’s going on. We need to treat them like any other patient. They need help.”

“These patients are the most misunderstood patients that we have. These are patients with illnesses. They are not completely aware of what’s going on. We need to treat them like any other patient. They need help.”

The number of facilities that provide inpatient psychiatric care has been dwindling for decades. As the American Psychiatric Association (APA) noted in its May 2022 report, “The Psychiatric Bed Crisis in the US,” in 1955, there were 337 inpatient beds per 100,000 people. By 2014, that figure had plummeted 91 percent to 29.7 beds per 100,000. The report also states that the “number of children with severe and acute mental health needs is beyond current treatment capacities.”

The APA report attributes the drop in psychiatric beds to “federal policy changes, the development of antipsychotic drugs, and the rise of managed care, among other factors.” The report also notes that while “overall spending on mental health treatment has steadily increased,” the percentage of mental health care spending on inpatient care dropped nearly 36 percent from 1986 to 2014 and “there are numerous barriers to inpatient care associated with current financing systems.”

The closure of behavioral health units is devastating for communities. Recently, the BHUs at Florida Medical Center in Lauderdale Lakes and Palmetto General Hospital in Hialeah, Fla. shut down in August and September, respectively. The closures represent Steward Health Care’s common practice of putting profits over patients and shuttering what they deem “unprofitable” units.

“I have worked in these units for 16 years and the need for psychiatric services has never been this high,” says Gladys Emekekwue, an RN who worked in Florida Medical Center’s BHU. “There are no other options for our patients. They don’t have transportation and are in no condition to travel long distances to seek care. Our patients will definitely be at great risk of suicide and self-harm.”

One twisted outcome of the loss of available beds is that today, the largest mental health facilities in the nation are jails, according to the continuing education class on America’s mental health crisis that National Nurses United offered last spring. (The class will be offered again, check the schedule on NNU’s website.) In the class, nurses learn stark, eye-opening facts, such as, if you have a mental illness, you are more likely to be incarcerated than hospitalized and that as many as one-third of the unhoused population has a serious mental illness.

Susan Beekman, RN at Mission Hospital Copestone, the BHU at HCA’s Mission Hospital in Asheville, N.C., notes that Dorothea Dix Hospital, the state’s first psychiatric hospital, closed its doors in 2012, a huge loss for people who needed long-term care. Founded in 1856 in the state capital of Raleigh, about 250 miles east of Asheville, its namesake was a pioneer in advocating for humane care for the mentally ill in the 19th century. Dix would no doubt be profoundly disappointed and appalled that 135 years after her death, the number of U.S. mental health facilities and services have decreased, not increased.

Today, Beekman’s facility has three adult inpatient behavioral health units and one for children and adolescents. She cares for adult patients from all across the Blue Ridge Mountains in the western part of the state. Beekman speculates that a lot of people that were at Dorothea Dix Hospital “came to the mountains.”

Rucker’s adult patients in Chicago get admitted to her facility’s BHU while children and adolescents get transferred to other hospitals or if they are wards of the state, they may get stuck in the ER because the Department of Children and Family Services can’t find a place for them. Rucker also comes across behavioral health patients in their 30s who had been living in nursing homes, their only option for care. They left the facility and realized they could not survive on the streets. To return to the nursing home, they need to be admitted to the hospital for an assessment.

The Covid-19 pandemic exacerbated the nation’s mental health crisis beyond measure. Our NNU nurse members working in behavioral health units see the most severe cases, where patients’ conditions have deteriorated past self management.

The pandemic completely disrupted people’s lives, livelihoods, and support networks. Weiss said “a lot of the patients have been sicker because of increased substance abuse, domestic violence, and food insecurity.” While some units, like the operating room or post anesthesia care, became ghost towns when Covid first hit, his unit has been full of patients since Covid began.

“People had trouble getting medications,” said Weiss. “They also had their own death and loss. They haven’t been able to have access to a psychiatrist. Some clinics don’t want to accept new patients, the wait times are too long, or they are considering therapy and there is no therapist available for them. So then the patients are even worse than they were prior to Covid.”

At hospitals, the scarcity of BHU beds only got worse due to the pandemic’s immense impact on mental health, lack of proper personal protective equipment, and outbreaks, which meant that units could not admit new patients at a time when every bed was needed. Nevertheless, the patients needed to go somewhere, which is another reason why some patients get sent to facilities far from home. And if staff were out sick, units were left extremely short staffed.

When the BHU at Glendale Memorial Hospital had outbreaks, despite patients initially having a negative PCR test, Weiss said they would stop admitting patients, test everyone again, keep them isolated in their rooms, and try to discharge them as soon as possible. Meanwhile, staff would be floated to other units as sitters for patients who needed one-to-one care. Once the unit was cleared, then they would start admitting patients again. The lack of beds means patients languish in the ED for days, weeks, or longer, waiting for an open bed.

At San Bernardino Community Hospital’s BHU, Clayton Dezan noticed many more young people being admitted, especially in the beginning of the pandemic, 18- to 24-year-olds, a far younger group than he was used to seeing. “They had a lot of fear and depression,” said Dezan, an RN who has been working in the BHU for a decade. “They didn’t have the same support as they did before the pandemic. They weren’t seeing other people and missed face-to-face contact.”

Dezan says many of the patients in his unit are unhoused and for some, their mental illness is drug-induced. Nearly all the patients in his unit are there on a 72-hour involuntary psychiatric hold, known in California as a 5150, for people who are a danger to themselves or others. He has also encountered patients who could barely breathe and even someone who complained of extreme pain but instead of being treated, was put on a 5150 hold. He says this can happen when patients say things like, “the pain is so bad I just want to die” or who are so agitated and screaming due to pain. When patients arrive with medical conditions that must be addressed immediately, Dezan contacts the house manager and advocates to move the patient to the appropriate unit.

Some of the 5150 patients get converted to a voluntary hold and remain longer if it is not safe to discharge them. If someone cannot care for themselves or is very violent, then they could be put under a conservatorship and then transferred to a locked facility for long-term care. However, it can take a long time to find an open bed. “Some have been in our unit for more than a year because we can’t find them a placement,” said Dezan.

In North Carolina, Beekman also encounters patients who need to be placed elsewhere because they can no longer function independently. “They have absolutely nowhere to go,” said Beekman who has been a nurse since 1991, including a decade in the Navy as a medical-surgical RN. “They are elderly so we have to find a nursing home or assisted living facility. Sometimes they end up staying in the behavioral health unit long-term because we need to have a place to send them to. You can’t send them to a shelter.”

When patients are discharged, a social worker should have a plan in place, including a place for them to go if they do not have a place to live. In California, they could go to a board-and-care home, which is a licensed adult residential facility for people with mental illness. However, many of these homes have been closing and some are in poor condition so people do not stay and are back on the streets, and then the cycle begins again. “I had one patient 36 times in three months,” said Dezan. “They go out and come back. The police bring them in.”

Patients keep getting readmitted due to the broken health care system, lack of resources, lack of affordable housing, and inadequate funding of programs and services. “We need more case managers to make sure that care is continued,” observed Dezan. “But if a patient is homeless, we can’t follow up with them until they come back. It’s hard to get them to see a psychiatrist on a regular basis. They have to have insurance, a place where they can be contacted, and they need to make time to go see them.”

Linda Rucker acknowledges that at Chicago’s Jackson Park Hospital, behavioral health patients have few options after discharge because there are no available outpatient services or board of health clinics anymore. Consequently, she sees many repeat patients, too. Sometimes they are people who are unhoused or who refuse to go to a facility. They have a psychotic break, get arrested, and end up in the ER again and again.

At the same time that Covid drove intense demand for BHU beds when there were fewer of them than ever, NNU behavioral health nurses faced new pandemic-related threats to their health and safety at work.

Because all BHU patients were supposed to test negative for Covid, some facilities did not give staff N95 respirators until much later in the pandemic because other hospital units, such as the ICU and ED, were prioritized.

Beekman in North Carolina said her unit only had surgical masks for the first year and a half of the pandemic. Then management announced in the fall of 2021 that part of her unit was going to care for Covid-positive behavioral health patients the next day. But they weren’t ready. Her unit did not have any negative pressure rooms and no one had been fit-tested for N95s. Beekman immediately asked her manager if the nurses were going to hear from infection control and they were fit tested that day. The Covid section of her unit only lasted a few months because Beekman said it was not set up for Covid patients. “We would be with these Covid patients wearing our masks and everything,” recalled Beekman. “Then we’d have to go get something from the supply room and there’s just one supply room on the unit. There was a lot of cross-contamination going on.”

Nowadays, Beekman said that if a patient does test positive, they have been good about staying in their room, which is important because behavioral health units typically have a common shared space with a TV. Patients in her unit are supposed to wear a mask, but not all of them comply. That’s the situation Weiss faces in Glendale, too. “It is difficult to keep people compliant wearing a mask depending on their situation,” said Weiss.

Weiss said BHU nurses at Glendale Memorial Hospital got N95s fairly quickly, but management was rationing PPE for more than a year and a half. Sometimes the PPE that nurses were fit-tested for were not available. Now, they have plenty of PPE but protections are still not optimal. Weiss, who has a beard, should wear a powered air-purifying respirator (PAPR) but still does not have one. He said PAPRs were prioritized for other units.

Dixon said that the bigger Sutter facilities got the majority of the PPE and that the nurses at Sutter Center for Psychiatry felt like they were the outlier. They were initially reusing N95s and getting substandard gloves. “We used to have to hunt down our manager to get an N95,” recalls Dixon who brought her own N95 at times because she lives with her 92-year-old mother and wanted to keep her safe. “Now they’re available at the door and we can get them whenever we want.”

When people find out that Laura Dixon works in behavioral health, she says the majority respond, “Wow. How can you do that?” because they think of the stereotype: patients who are unpredictable, highly psychotic, violent, wearing restraints, or who are criminally insane. Sadly, these stigmatizing descriptions and images are still prevalent. “A lot of people have the idea from Hollywood that everyone’s gonna come and jump you and just attack you out of the blue,” said Weiss. “But people could be attacked on the streets or in the subway more than they would be in my unit.”

The reality of workplace violence in behavioral health units is very different. Yes, workplace violence is still a problem — as it is throughout the entire hospital — and there is much that employers can improve — such as boosting staffing levels — to prevent it from happening in the first place.

Nurses know that workplace violence and behavioral health issues can occur in any unit in the hospital, not just the BHU. RNs encounter patients or visitors who react violently to different situations, whether it’s a furious family member in the emergency department, a confused patient in med-surg, a psychotic patient with substance abuse issues, or a screaming patient in the ICU, the list goes on. “Every floor in the hospital is going to have a behavioral health issue,” observes Weiss. “People on other floors may be attacked because of how they interact with the patient. L&D can be dangerous because you don’t know what’s going to happen with the birth.”

But psych nurses are probably the best educated and equipped to handle potentially violent people.

“I believe behavioral health is one of the safest places in the hospital,” stated Beekman. “Behavioral health nurses know how to interact with the agitated. We validate the person, we have a therapeutic relationship, and we never get into a power struggle with a patient.“

To be sure, it can be very challenging when patients are intensely demanding and act out by screaming, hitting, or spitting. But Rucker, who has worked at Jackson Park for 40 years, including 14 years as an LPN, also says that it’s a misconception that her job as a behavioral health RN in the emergency department is always dangerous and that there is constant fighting. “I have never been hit, not one time” said Rucker, who has only had one injury in the ED. “I was putting a patient in restraints and the side rail went down and broke my finger. The patient didn’t break it.”

Rucker says her hospital has sitters for all of their psychiatric patients in the ED and they let her know if someone is pacing, agitated, or talking to themselves. This level of staffing is key to workplace violence prevention in her hospital. She will talk to the patients and if they are hearing voices that others cannot, she will ask them which arm they would like the shot to help them calm down. “Don’t wait until they are screaming,” advised Rucker, who notes that if you wait too long, the patient may no longer have control over themselves.

California has a workplace violence prevention law, fought for by California Nurses Association (CNA), mandating that health care employers have employee input on unit-specific plans to prevent workplace violence, report incidents of violence and threats of violence, and provide training, among other requirements. The federal workplace violence prevention bill, which passed in the U.S. House of Representatives last year (H.R. 1195) and was introduced in the U.S. Senate this year (S. 4182), is modeled on California’s landmark bill.

Weiss is not only the charge nurse in his unit, he is also part of the code gray response team called to de-escalate situations in other parts of the hospital. In some cases, he has been able to get the situation quickly resolved by having a conversation with the patient and discovering that they were acting out because they were bored or because they heard voices in their head that others cannot hear. Once the bored patient was given something to do, they were fine. And the patient who heard voices wanted it to stop, so Weiss got them the proper dose of medication.

Among the unhoused patients, Weiss notes that some take meth, not because they want to get high but because they want to stay awake and are afraid to sleep on the streets and get their belongings stolen or beaten up by others. “But unfortunately, the side effect of meth is psychosis,” said Weiss, who acknowledges that some of the repeat patients make the rounds of hospitals because they have nowhere else to go and they know they will have a place to sleep and regular meals in the BHU.

Weiss observes that knowing crisis de-escalation tactics, having transparent communication, providing consistency of care, and having a willingness to build rapport with a patient are all important to reducing workplace violence. Of course, Weiss conceded that unpredictable, violent outbursts do occur in behavioral health units when patients are hallucinating or have impulse control disorder.

Of course, what’s key to preventing workplace violence in BHUs and all units is appropriate and even robust staffing of RNs and ancillary health workers, like sitters.

Ever since Weiss began working at Glendale Memorial Hospital in 2016, he has been consistently demanding that management take action to make his unit safer. After Weiss’ numerous emails and bringing up safety issues at countless professional practice committee (PPC) meetings over many months, the BHU got convex safety mirrors installed to eliminate blind spots, a much-needed second restraint bed, and the implementation of duress alarms.

When Dixon’s Sutter facility faced a big upsurge in workplace violence and inadequate staffing for the acuity of patients, they decided to organize to have a say in their working conditions, patient care, and RN retention. In December 2020, they voted to join CNA. Retaining staff and safe staffing are paramount in their bargaining for a first contract. “We rely on each other very heavily for de-escalating patients,” noted Dixon, who has been kicked, bitten, and hit by patients. “Having high turnover can be dangerous for us.”

“Not having proper staffing is always a struggle,” added Dixon, who says that Sutter’s acuity system is based on a medical model and does not necessarily correlate to the patient’s psychiatric condition. “Nurses would be canceled and as the census goes up, the potential for workplace violence goes up as well.”

Staffing is a huge concern for all the nurses interviewed. Susan Beekman reports that her adult BHU does primary nursing and their RN-to-patient ratio is usually 7 to 1. Whenever they go out of ratio, Beekman said, “I get out the ADO and turn it in.”

The other two adult units at Copestone use “team” nursing, with just two RNs and three or four techs for 17 to 18 patients. One nurse provides all the medication and the other staff provide care. “They need another nurse on each of those units,” observed Beekman, especially if there is a behavioral health emergency. “I’ve always spoken out against team nursing because it’s trying to do more with less.”

Nurses at Mission have been holding protests and rallies for more than a year to bring attention to dangerous short staffing and the critical need to retain experienced nurses. In September, the National Nurses Organizing Committee RN members won significant raises, a big victory, which will help with retaining and recruiting nurses. Beekman said the raises are a good start, but she would also like to see a commitment to safe staffing.

Dorothea Dix would undoubtedly be proud and gratified that the nurses interviewed for this article care deeply about their patients. Beekman was drawn to behavioral health after her experience helping unhoused people at Good News Rescue Mission in Redding, California. “A lot of them had mental illness, substance abuse issues,” observed Beekman, who has also worked in labor and delivery, the ICU, and PACU. “I liked working with those people and saw how they really needed a hand up.”

Chuleenan Svetvilas is a communications specialists at National Nurses United.