Public-sector RNs fight back

Staff report

National Nurse magazine - July | August | September 2024 Issue

Nurses know that public-sector hospitals and clinics are vital to their communities because they often serve the most vulnerable patients. That’s why they are often called safety-net facilities because people can get care regardless of their ability to pay or their immigration status. Meanwhile, corporate health systems, including so-called nonprofit systems, do not treat anywhere near their fair share of Medi-Cal (the state’s Medicaid system) patients.

In California, public health care systems serve more than 3.7 million patients annually, including 35 percent of all Medi-Cal and uninsured hospital care statewide, according to the California Association of Public Hospitals and Health Systems. Their services are essential but across the state, many public hospitals are under attack. Nurses are fighting unit closures, staffing cuts, potential sale to private operators, and more.

According to the Stanford Institute for Economic Policy Research, a formerly government-run hospital admitted on average 15 percent fewer Medicaid patients in the years immediately following privatization. Privatization means less care for vulnerable patients.

Here’s a snapshot of what is happening at public-sector hospitals from San Bernardino County in the southern part of the state to Alameda County, which is in the San Francisco Bay Area. Nurse members of California Nurses Association (CNA) at these facilities are speaking out, standing up for patients, their communities, and themselves.

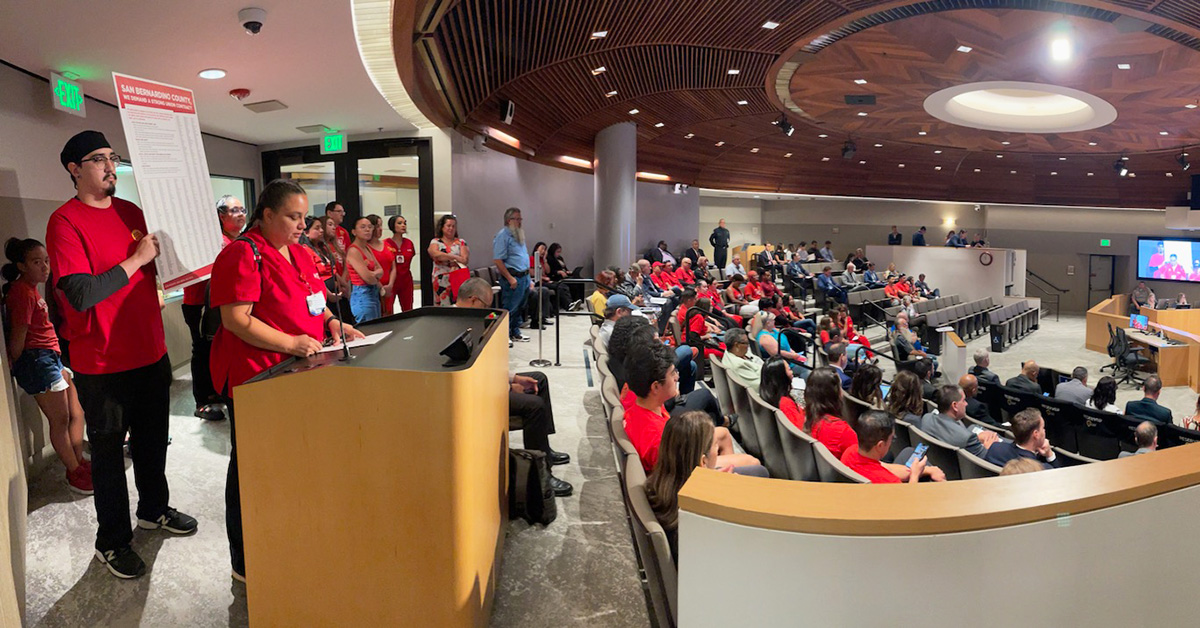

San Bernardino County

Registered nurses who work for San Bernardino County came out in force in August to attend a board of supervisors meeting and to speak out during public comment at the board of supervisors meeting in San Bernardino, Calif. They highlighted their patient safety concerns, including chronic short staffing and the county’s failure to recruit and retain RNs.

The nurses said that chronic short staffing is leading to moral distress, resulting in nurses leaving. There are currently more than 300 open nurse positions at Arrowhead Regional Medical Center (ARMC), the hospital operated by San Bernardino County.

“Over the past six months, nurses at ARMC have reported more than 125 incidents of unsafe patient care due to short staffing,” said Diana Lucatero, RN in the medical intensive care unit at ARMC. “This is unacceptable. We must stand behind our hospital’s mission statement and make the necessary changes to provide our community with a hospital that focuses on maintaining the highest standards in patient care. The safety of our patients needs to be the top priority.”

The union nurses are currently in bargaining and are demanding a strong contract to address their patient safety concerns. The RNs’ current contract expires in October 2024 and covers San Bernardino County nurses who work at ARMC, the Department of Public Health, the Department of Behavioral Health, the sheriff’s department, the probation department, and other county facilities.

The RNs called on the San Bernardino County Board of Supervisors to support nurses’ bargaining demands for the highest standards in patient safety and the recruitment and retention of nursing talent.

Ventura County

Nurses and health care workers from Ventura County held an informational picket in September to protest the Board of Supervisors’ decision to approve the closure of the Santa Paula Hospital intensive care unit (ICU) and obstetrics unit. Staff from Santa Paula Hospital in Santa Paula, Calif., and staff from Ventura County Medical Center, in Ventura, Calif., joined together to oppose the closures. After the picket, nurses also spoke out at the Board of Supervisors meeting.

Nurses wanted the public to know that serious problems can arise when laboring mothers or critically ill patients are forced to transfer from one hospital to another because of service shutdowns at their local facility. Furthermore, they noted that, currently, without the need for these transfers, patients are often already forced to wait long periods for an ambulance.

“Right now, when we are dealing with emergency situations, we have seen people wait too long for ambulances to take them to Ventura County Medical Center from Santa Paula,” said Mary Ann Chase, an RN at Santa Paula. “This problem can only get worse if these units end up closing. This is unacceptable when we are talking about people’s lives and well-being. These proposed closures will overwhelm other surrounding area hospitals and put the Santa Clara Valley patients at risk of delayed lifesaving care.”

Los Angeles County

Registered nurses at Antelope Valley Medical Center (AVMC) in Lancaster, Calif., spoke out at the Antelope Valley Healthcare District (AVHD) Board of Directors meeting in July to demand safe staffing and a strong union contract that prioritizes recruitment and retention. In June the nurses picketed to protest chronic short staffing.

Understaffing is a major concern for nurses at AVMC, which has one of the busiest ERs in the country. The night shift at the ER will sometimes be staffed with fewer than 10 RNs for more than 100 patients, jeopardizing patient care. Additionally, nurses throughout the hospital are being pressured to work overtime after their 12-hour shift has ended due to the next shift being understaffed. Nurses are also being floated to work in units outside of their area of expertise, which is not safe for patients or nurses. Additionally, nurses throughout the hospital have filed dozens of assignment despite objection forms (ADOs), reporting unsafe staffing and missed meal and rest breaks.

“Our home units are where we provide the best, specialized care to the area’s highly acute patients,” said Brandi Wechsberg, post-anesthesia care unit RN at AVMC. “Floating a recovery room nurse to the ER, which could occur under the hospital’s proposal, would not be safe for our patients and it would put our nursing license at risk.”

San Benito County

Since 2022, registered nurses from Hazel Hawkins Memorial Hospital in Hollister, Calif., have been fighting to keep all service lines open. The Board of Directors of the San Benito Health District filed for Chapter 9 bankruptcy and made moves to sell the hospital to a private entity. Nurses fought back and in March 2024, a district court judge dismissed the San Benito County Health Care District’s assertion of bankruptcy, stating that the district “failed to show it is insolvent. The judge’s decision aligns with the findings of a 2023 report commissioned by San Benito County, which found that Hazel Hawkins “does not need to be in bankruptcy or sold to a for-profit provider.”

Fortunately, the San Benito County Board of Supervisors agreed with the nurses that Hazel Hawkins should remain a public facility. In July 2024, Hazel Hawkins nurses attended a San Benito County Board of Supervisors special meeting to discuss their ongoing concerns about patient safety and the future of the public hospital.

“Nurses want to thank the board of supervisors for the heavy lifting they are doing to underscore to the public why it is important to keep Hazel Hawkins Memorial Hospital a public institution and why a sale to a private entity is harmful and unwarranted,” said Arihanna Sanchez, a registered nurse in the emergency department. “As nurses whose main concern is the health and welfare of the public, we know that public oversight is critical to ensure that the needs of our community are met.”

Now there are two measures on the November ballot that will affect the future of the hospital: One measure, which the nurses support, would form a new, separate entity called a “Joint Powers Authority,” which would keep the hospital under local control. The other measure, which RNs oppose, would lease and irrevocably sell San Benito County’s only hospital to a not-for-profit “shell” company controlled by an unknown and unproven for-profit company.

Alameda County

In June, registered nurses at Alameda Hospital in Alameda, Calif. picketed outside the hospital to pressure hospital and county leaders to reverse dangerous cuts to patient care. Alameda Health System (AHS), which has served the East Bay community for 160 years, planned to shut down all surgical services at the hospital by October.

In September, nurses at Alameda and San Leandro hospitals, both part of AHS, held a rally and speak-out at the AHS Board of Trustees meeting in Oakland, Calif. to highlight their patient safety concerns, including cuts to staffing, and AHS’ failure to meaningfully address these serious issues during bargaining.

“Throughout negotiations, our goal has been to address the working conditions that drive us away from the bedside so we can retain experienced nurses and attract new ones,” said Mawata Kamara, RN in the emergency department at San Leandro Hospital and a CNA/NNOC board member. “Unfortunately, AHS has neglected to take this process seriously.”

For the past several months, nurses have proposed improvements to workplace violence safety, improved staffing, and protections to ensure technology is used to enhance nursing practice, not undermine nurses’ ability to provide safe patient care. Nurses say AHS has failed to address nurses’ staffing concerns; instead, management has focused on cost-cutting measures and the closure of surgical units at Alameda Hospital.